This is the fourth article in a series that looks at the five best players at each position for the Pittsburgh Pirates. In this installment are outfielders.

In terms of outfielders, the Pirates have enough talent to make almost every other team jealous. Pittsburgh’s list includes seven Hall of Famers and two others that many fans argue should be in Cooperstown. Although right field may be the “weakest” of the three positions in terms of depth, the Pirates boast two of the greatest throwing arms in major league history.

The Best Outfielders in Pittsburgh Pirates History

Left Fielders

Honorable Mentions – Elmer “Mike” Smith began his career as a pitcher with the American Association’s Cincinnati Red Stockings going 69-50 overall and leading the league with a 2.94 earned run average in 1887. He converted to the outfield after joining the Pirates in 1892, finishing with at least 120 runs and 175 his in three of his seven seasons (1892-97 and 1901). Arguably Smith’s best year was 1893, when he batted .346 with 121 runs and 26 stolen bases and set career highs with 179 hits, 23 triples, seven home runs and 103 runs batted in. He finished his career in Pittsburgh with a .325 average, 644 runs, 960 hits, 130 doubles, 99 triples, 30 homers, 469 RBIs, 174 steals (including six seasons with 20 or more) and 1,378 total bases in 766 games. Smith had second stints with both with Cincinnati and Pittsburgh, plus spent parts of seasons in New York and Boston. He retired in 1901 and passed away in 1945 at age 77.

Carson Bigbee spent his entire 11-year career with the Pirates (1916-26) after getting his start in the Pacific Northwest. Despite being an injury-plagued player, he was productive, posting at least 100 runs and 200 hits twice and stealing more than 20 bases four times. Bigbee’s best season was 1922, when he set career highs with a .350 average, 113 runs, 215 hits, five home runs and 99 runs batted in. His playing time declined later in his career, with injuries playing a part. Bigbee’s biggest claim to fame came in the eighth inning of Game 7 of the 1925 World Series. He drove in the tying run off future Hall of Famer Walter Johnson and later scored the title-clinching run.

Despite this, his career came to an abrupt end in 1926 after what became known as the “ABC Affair.” Former manager and then-vice president Fred Clarke was sitting on the bench, and he began to give input on lineup decisions to manager Bill McKechnie, one of which was to bench Max Carey. Bigbee, his best friend and potential replacement, heard the conversation between the two, told Carey and team leader and pitcher Babe Adams, and the three voiced their displeasure, calling for a vote to remove Clarke from the bench. McKechnie supported the vice president, the vote failed, and the three players were disciplined, with Adams and Bigbee released, never to play in the major leagues again and Carey was waived the following year. Bigbee played three seasons in the Pacific Coast League, worked as an auto salesman, owned a grapefruit ranch and managed in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. He passed away in 1964 at age 69.

Bob Skinner joined the Pirates in 1954 and, after a year in the minors, returned to Pittsburgh and moved from first base to the outfield. He was part of a group of young players working to turn the Pirates around in the late 1950s and was a productive left-handed spark in the lineup. Skinner earned three All-Star selections in nine years in Pittsburgh (1954 and 56-63), with his best season coming in 1958, when had 13 home runs, 70 RBIs and set career highs with a .321 average, 93 runs and 170 hits. He had another solid year in 1960 but missed five games in the World Series after jamming his thumb on a slide. After a rough year, Skinner rebounded to bat .302 and hit a personal-best 20 home runs in 1962. With the team dropping in the standings, he was traded to the Reds, finishing his Pirates career with a .280 average, 574 runs, 1,050 hits, 173 doubles, 90 homers, 462 RBIs and 1,597 total bases in 1,100 games. Skinner also spent time with the Cardinals, retired in 1966, had brief runs as manager of the Phillies and Padres and was a hitting coach with several organizations, including the Pirates when they won the World Series in 1979. He spent more than 30 years as a coach and manager and 20 more as a scout with the Astros. His son, Joel, was a catcher and later a manager with the Indians.

Al Martin had the unenviable task of replacing a legend in the Pirates’ outfield, but he had experience in that role since he was the nephew of NFL All-Pro linebacker and two-time champion Rod Martin. He posted solid offensive numbers over eight seasons (1992-99), earning some Rookie of the Year consideration in 1993. Martin had his best offensive season three years later, when he hit 18 home runs and set career highs with a 300 average, 101 runs, 189 hits, 40 doubles, 72 RBIs and 38 stolen bases. After posting a career-best 24 homers in 1999, he was traded to the Padres and was a member of the 116-win Mariners squad in 2001. Martin went unsigned the following year, then played with the Devil Rays and finished his career in Korea in 2004. He was the subject of several controversies throughout his career including making false claims about playing football at USC and being selected to the 1994 All-Star Game, as well as pleading guilty to domestic violence charges and then lying about it to the press in Seattle.

Brian Giles showed flashes during his time with the Indians but blossomed into a star after his trade to the Pirates. He played five seasons in Pittsburgh (1999-2003), earning three All-Star selections, hitting at least 35 home runs four times and batting over .300 with at least 100 runs, 160 hits and 100 RBIs three times each. Giles is the all-time Pirates leader in slugging percentage (.591), ranks second in on-base percentage (.426) and seventh in home runs (506) to go with a .279 average, 501 runs, 782 hits, 174 doubles, 506 RBIs and 1,503 total bases in 715 games. He was traded to the Padres in 2003, putting up solid numbers in a pitcher’s park before arthritis in his knee forced him to retire in 2009. Giles had two blemishes on his record, a domestic violence lawsuit brought about by a former girlfriend and a claim of Adderall use (a banned substance under baseball’s steroid policy) by former teammate, catcher Jason Kendall. Giles has maintained his innocence and did not test positive during his playing career.

Starling Marte is a Dominican Republic native who signed with the Pirates in 2007. During his five minor league seasons, he appeared in the MLB All-Star Futures Game in 2011 and joined Pittsburgh late the following year. In his time with the Pirates, Marte earned two gold gloves and an All-Star selection after batting a career-best .311 in 2016. The following year, he was suspended 80 games after a positive test for a performance-enhancing substance but rebounded with back-to-back seasons of at least 20 home runs, including a career-best 23 in 2019. Marte was traded to the Diamondbacks before the 2020 season, finishing his Pirates career with a .287 average, 555 runs, 1,047 hits, 192 doubles, 108 homers, 420 RBIs, 239 steals (including five seasons with 30 or more) and 1,647 total bases in 953 games. In the playoffs, he appeared in eight games, totaling two runs and four hits, including a home run. The 2015 Wilson Defensive Player Award winner played with the Marlins and Athletics before having a bit of a resurgence after joining the Mets, earning an All-Star selection in his first season in New York in 2022.

Bryan Reynolds was drafted by the Giants in the second round in 2016 and traded to the Pirates two years later for Andrew McCutchen. After batting a career-best .314 and earning Rookie of the Year consideration in 2019, he fell off considerably during the COVID-shortened season. Reynolds returned to form in 2021, earning his only All-Star selection to date after batting .302, setting career highs with 93 runs, 35 doubles and 90 RBIs and leading the league with nine triples. He has continued his solid production, posting a .278 average, 359 runs, 651 hits, 128 doubles, 98 home runs, 323 RBIs and 1,119 total bases in 638 games through 2023. Before that season, Reynolds signed an eight-year, $106.75 million contract, the richest in Pirates’ history, giving him plenty of time to move higher on this list.

5. Jason Bay – The British Columbia native was drafted by the Expos and traded three times before landing with the Pirates in 2003. Bay had surgery on his shoulder and returned to become the first Pittsburgh player and first Canadian to win the Rookie of the Year Award the following season after posting a .282-26-82 stat line. The campaign of his first of five straight with 20 homers, and he totaled at least 100 runs, 160 hits and 100 RBIs three times in that span. Bay had a down 2007 season but rebounded the following year before being sent to the Red Sox in a three-team deal that saw Manny Ramirez get moved to the Dodgers. The two-time All-Star and 2005 fielding champion ended his Pirates career with a .281 average, 435 runs, 729 hits, 151 doubles, 139 home runs, 452 RBIs and 1,333 total bases in 719 games.

Bay had a stellar season with the Red Sox and turned that into a massive contract with the Mets before the 2010 season. Injuries and inconsistent play derailed his time in New York, and he finished his career with Seattle in 2013. Bay played in the Little League World Series and World Baseball Classic for his native country and was inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 2019.

4. Barry Bonds – He was the child of Bobby Bonds, a star athlete who signed his first contract with the Giants two weeks after his son was born. While Bobby was playing in San Francisco, Barry got to hang out in the clubhouse and met several players, including his godfather and future Hall of Famer Willie Mays. Barry became a baseball star at Arizona State and was drafted sixth overall by the Pirates in 1985. He started as a leadoff hitter, using his speed to steal at least 30 bases six times in seven seasons with Pittsburgh (1986-92). Bonds showed flashes of power that were realized when he was moved to fifth in the batting order in 1990. He responded with a .301 average, 33 home runs and 114 RBIs to win the MVP Award as well as a gold glove, silver slugger and All-Star selection. While he wasn’t an All-Star the following year, his numbers were similar, with a .292-25-116 stat line earning him an MVP runner-up spot.

Bonds solidified his status as one of the best players in the game with a second MVP Award in three years after batting .311 with 34 homers, 103 RBIs and league-leading totals of 109 runs, a .458 on-base percentage, a .624 slugging percentage and 365 total bases in 1992. In addition, the outfield of Bonds, Van Slyke and Bonilla led the Pirates to three straight division titles, although they lost in the NLCS each time. Bonds appeared in 20 playoff games, totaling 10 runs, 13 hits one home run, three RBIs and six steals. His time in Pittsburgh came to an end after a heartbreaking loss to the Braves in the NLCS and he signed what was then baseball’s biggest contract (six years, $43 million) with the Giants. Bonds’ time in Pittsburgh included two MVPs, two All-Star selections, three gold gloves and three silver sluggers. He batted .275 with 672 runs, 984 hits, 220 doubles, 176 homers (fifth in franchise history), 556 RBIs, 251 stolen bases (seventh) and 1,804 total bases in 1,010 games.

Bonds spent the final 15 years of his illustrious career in San Francisco, winning five more MVP awards, including four straight from 2001-04, despite pushing 40 years old. He was such a feared hitter that he led the league in walks and intentional walks 12 times, including an astonishing 120 in 2004, when he set the major league record with 232 free passes. Bonds made history in 2001, setting another record with 73 home runs at the height of the Steroid era. He finished his 22-year career with all-time records in home runs (762), walks (2,558) and intentional walks (688) to go with 2,227 runs (third on the all-time list), 5,976 total bases (fifth), 1,996 RBIs (sixth), 2,935 hits, 514 steals and a .298 average. Despite all of these accolades, including seven MVP Awards, 14 All-Star selections, 12 silver sluggers, eight gold gloves and two batting titles, Bonds’ links to both performance-enhancing drugs and the BALCO lab (as well as an unpleasant attitude towards both fans and the media) have kept him out of the Baseball Hall of Fame. He will be a 2024 inductee into the Pirates Hall of Fame, but his call to Cooperstown will have to wait at least until the next Contemporary Baseball Era vote in 2025.

3. Ralph Kiner – The New Mexico native signed with the Pirates out of high school in 1941 and quickly showed off his power. After spending three years as a Navy pilot flying antisubmarine missions over the Pacific Ocean during World War II, Kiner joined Pittsburgh, playing center field and leading the league with 23 home runs in 1946, the first of seven straight times he did so in that category. He moved to left the following year and continued his power surge, hitting 51 homers while scoring 118 runs, driving in a career-high 127, batting .313, rapping a personal-best 177 hits and leading the National League with 361 total bases. Kiner had arguably his best offensive season in 1949, when he batted .310, matched his total bases mark, scored 116 runs had 170 hits and led the league with 54 home runs, 127 RBIs and a .658 slugging percentage to finish fourth in the MVP race.

The Pirates were a solid team and, as their star, Kiner, with his five straight seasons of at least 100 runs score and 100 RBIs, reaped the benefits off the field. He built a house in Palm Springs, was a part of co-owner Bing Crosby‘s inner circle and married tennis star Nancy Chaffee. However, when the Pirates fell to last place in 1950, general manager Branch Rickey started trying to trade Kiner, despite him being the primary reason fans even showed up to games. When Kiner helped the players get increased pension benefits from owners, he was finally traded to the Cubs in June 1953. The five-time All-Star finished his eight-year Pirates career (1946-53) ranked second in franchise history in home runs (301) and slugging percentage (.567), fifth in walks (795) and seventh in RBIs (801) to go with a .280 average, 754 runs, 1,097 hits 153 doubles and 2,217 total bases in 1,095 games.

Kiner was an All-Star after the trade, but back issues caused his power numbers to decline. He was sold to the Indians but retired after the 1955 season to run the team’s Pacific Coast League affiliate, the San Diego Padres. Kiner also became a broadcaster, first in San Diego, then with the White Sox. In 1962, he joined the expansion Mets in the booth, forming a legendary trio with Lindsey Nelson and Bob Murphy. Kiner, with his popular Kiner’s Korner postgame show, stayed with the Mets until 2013, working an abbreviated schedule after suffering a stroke. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame by one vote in 1975, his 15th and final year on the baseball writers’ ballot. Kiner passed away in 2014 at age 91.

2. Fred Clarke – The midwestern farm boy got his major league start with the Louisville Colonels in 1894 and was a part of the Barney Dreyfuss-orchestrated trade to the Pirates at the turn of the 20th century. Clarke was the team’s player-manager throughout his entire 15-year career with Pittsburgh (1900-11 and 13-15) and spent his time in the field as a hard-nosed player, physically breaking up double plays and getting in scuffles with opposing players. He was a terror at the plate as well, stealing at least 20 bases eight times, batting over .300 six times, smacking at least 150 hits on four occasions and scoring more than 100 runs twice. Clarke batted .324 with 118 runs, 171 hits and 60 RBIs in 1901 and had arguably his best season two years later, when he hit .351 with 150 hits, 70 RBIs and led the league with 32 doubles and a .532 slugging percentage.

“Cap” was a part of four pennant-winning teams and played in two World Series, getting several clutch hits during the team’s first title win in 1909 and totaling 10 runs, 13 hits, two home runs, seven RBIs and four stolen bases in 15 postseason contests. He focused his time solely as a manager and played just 12 games over the next three seasons. Clarke ranks fifth in franchise history in triples (156), sixth in stolen bases (261), eighth in runs (1,015) and tenth in hits (1,638) to go with a .312 average, 238 doubles, 33 home runs, 622 RBIs and 2,287 total bases in 1,479 games. He was also stellar on defense, winning three fielding titles and leading the league in putouts three times. Clarke retired after the 1915 season, amassing 13 winning seasons and a 1,422-969 record as a manager, including a club-record 110 wins in 1909.

Clarke became rich when oil was found on his Kansas ranch and used some of the money to buy a stake in the Pirates, becoming their vice president in 1925. He sat on the bench during games and was an inspiration to the team, which won the World Series that year. However, his presence created some issues, and he was a part of the “ABC Affair” in which three players tried to vote him out of the dugout, leading to their removal from the team. Clarke resigned his vice president post and sold his stake in the team after the 1926 season. He spent his life off the field on his ranch designing baseball equipment and working as the president of the National Baseball Congress, an organization that runs a 10-day tournament for community-based teams throughout the U.S. He was voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Old Timer’s Committee in 1945 and passed away after a bout of pneumonia in 1960 at age 87.

1. Willie Stargell – His childhood included his father leaving before he was born, living with his grandfather (who was the son of a slave) for a time, then living with an overbearing aunt for six years while his mother tried to get her life in order. Stargell signed with the Pirates in 1958 and made his brief big-league debut four years later. He had issues with his weight and at the plate early in his career, and his play in the field was less than stellar thanks to knee issues which could be traced back to football injury suffered in high school. Stargell worked on improving his hitting, especially against lefties, and his use of a bigger bat helped him fix holes in his swing. He had 15 seasons with at least 20 home runs, including 13 in a row from 1964-76), and he drove in 100 runs five times in his 21-year career spent entirely with Pittsburgh (1962-82).

Although he earned three All-Star selections early in his career, Stargell’s game picked up considerably after the Pirates moved into Three Rivers Stadium in 1970. He batted .295 with 104 runs, led the league with 48 home runs and drove in a career-best 125 runs in 1971, which led to a runner-up finish in the MVP voting. In the playoffs, he had five hits in the World Series, helping the Pirates beat the Orioles for their first title in more than a decade and their fourth overall. The following year at first base, Stargell finished third in the MVP voting after posting a .293-33-112 stat line. He returned to the outfield in 1973 and finished second in the MVP race again despite batting .299, setting career highs with 106 runs and 337 total bases and leading the league with 44 homers, 119 RBIs and a .646 slugging percentage.

“Pops” played one more season in left field in 1974, then returned to first base for the rest of his career. He faced injury issues later in his playing days, especially his knees, hamstrings, ribs and elbows which caused his power to decline. Stargell had a resurgence in 1979, winning the MVP Award after hitting 32 home runs, then becoming the first player to be named MVP in both the NLCS and the World Series, leading the “We Are Family” Pirates to another victory over the Orioles for their fifth championship. That season, he had nine runs, 17 hits, six doubles, five home runs and 13 RBIs in 10 playoff games.

Stargell’s playing time declined over his final three seasons, and he retired in 1982, spending time as a coach and instructor with the Braves and Pirates. He batted .292 with 55 triples and is the all-time franchise leader in home runs (475), RBIs (1,540), walks (937) and strikeouts (1,936), ranks third in games (2,300), slugging percentage (.529) and total bases (4,190), fourth in doubles (423), fifth in runs (1,194) and seventh in hits (2,232). The seven-time All-Star appeared in 36 postseason games, totaling 18 runs, 37 hits, 10 doubles, seven home runs and 10 RBIs. He also won a fielding title (1971) the Gehrig and Clemente Awards (1974), the Hutch Award (1978) and the Ruth Award for best playoff performance (1979). Stargell, who was a hero to the black community of Pittsburgh off the field, was voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1988 and passed away after having a stroke following gallbladder surgery in 2001 at age 61.

Center Fielders

Honorable Mentions – Jake Stenzel was the son of German immigrants who settled in Cincinnati. After one season with the Cubs and another in the minors, he joined the Pirates, playing three games in 1892. Two years later, he developed into a productive player, providing Pittsburgh fans with four straight seasons of at least a .350 average, 100 runs, 170 hits, 80 RBIs and 50 stolen bases. Arguably his best of the bunch was 1894, possibly the single greatest offensive season in baseball before 1900. That year, Stenzel batted .352 with 185 hits and 61 steals, and he set career highs with 150 runs, 20 triples, 13 home runs, 121 RBIs and 303 total bases. In five seasons with the Pirates (1892-96), he set franchise records in batting average (.360) and on-base percentage (.429) and ranks fourth in slugging percentage (.528) to go with 425 runs, 631 hits, 116 doubles, 26 homers, 337 RBIs and 188 stolen bases in just 439 games. Stenzel played with Baltimore, St. Louis and Cincinnati, retiring in 1899. He returned to Cincinnati and ran a bar across from Crosley Field until World War I and worked as a night watchman as a factory until he passed away due to influenza in 1919 at age 51.

Tommy Leach was an inside-the-park home run specialist and the longest-surviving player from the 1903 World Series. He was primarily a third baseman during his 14-year Pirates career but was the starter for five years in center (1907 and 09-12). Leach batted .303 with 102 runs and career-high totals of 166 hits and 43 stolen bases in 1907 and two years later, he led the league with 126 runs. During his two World Series appearances, he batted .310 with 11 runs, 18 hits, four doubles, four triples and 10 RBIs in 15 games, helping Pittsburgh beat Detroit in 1909. The two-time fielding champion was a minor league manager and a scout with the Braves. Leach passed away in 1969 at age 91.

Although he was overshadowed by his two younger brothers, Vince DiMaggio earned two All-Star appearances during a 10-year major league career, with five seasons spent in Pittsburgh (1940-44). He wasn’t a power hitter like either of his brothers and led the league in strikeouts six times, including a then-record 138 with the Boston Bees (later Braves) in 1938. The son of Italian immigrants was more outgoing than his brothers but just as good in center field, where he led the league in assists three times and putouts twice during his time with the Pirates after coming over from the Reds in a trade early in the 1940 season. DiMaggio’s following year was his best at the plate, batting .267 and setting career highs with 20 home runs and 100 runs batted in. He was traded across Pennsylvania to the Phillies after the 1944 season, finishing his Pirates career with 588 hits, 136 doubles, 79 home runs and 367 RBIs in 670 games. DiMaggio finished his major league career with the Giants in 1946 and spent five more years as a minor league player-manager. His retirement years were spent helping run the family restaurant in San Francisco, driving a milk truck, selling liquor and brushes and bass fishing. DiMaggio passed away from colon cancer in 1986 at age 74.

Frank Thomas was the son of a Lithuanian immigrant who changed his last name from Tumas when he entered this country. Thomas originally went into the seminary but turned instead to baseball and was signed by the Pirates in 1948. After a pair of brief call-ups, he was in the major leagues on a full-time basis in 1953, after Kiner was traded away. Thomas was his replacement in the lineup, especially in the power department, and he slugged 20 or more home runs in each of his six full seasons with Pittsburgh. The three-time All-Star played most of his early time in center but also spent time at both corner infield and corner outfield spots. Like Kiner before him, Thomas knew his worth as a player despite playing on a long-suffering team, and he had many contract squabbles with Branch Rickey over his salary. After the 1958 season, he was traded as part of a seven-player deal to the Reds but his only season with Cincinnati was negatively affected by a hand injury. In eight years with the Pirates (1951-58), “Big Donkey” batted .275 with 473 runs, 950 hits, 159 doubles, 163 home runs, 562 RBIs and 1,638 total bases in 925 games. He spent time with five other teams over his final six seasons, including two years with the expansion Mets and another with the Phillies during their collapse in 1964. Thomas’ career came to an end after a second stint with the Cubs in 1966. He was a longtime participant in Pirates fantasy camps and passed away in 2023 at age 93.

Another Pirate from a trio of famous baseball brothers was Matty Alou, who started his career with the Giants and was traded across the country after the 1965 season. The Dominican-born Alou played for the nation’s government-supported Air Force baseball team as a 17-year-old. The conditions were less than idea and, after losing a doubleheader, the entire team (including future Hall of Famer Juan Marichal) was jailed for five days. Following the trade, he had an impressive first season with Pittsburgh, amassing 86 runs, 183 hits and winning his only batting title with a .342 average. Alou was a two-time All-Star who had his best season in 1969, when he batted .331, scored a career-high 105 runs and led the league with 231 hits and 41 doubles. To make room for the next player on this list, he was traded to the Cardinals, ending his five-year run with the Pirates (1966-70) with a .327 average (fifth in franchise history), 434 runs, 986 hits, 129 doubles, 202 RBIs and 1,201 total bases in 743 games. He also had three hits in a loss to the Reds in the 1970 NLCS. Alou played for five teams over his final four major league seasons, winning a title with the Athletics in 1972, then spending three years in Japan and several more in his native country. He was a scout for the Tigers and Giants and was honored with an induction into the Hispanic Heritage Baseball Museum Hall of Fame in 2007. Alou passed away after suffering a stroke in 2011 at age 72.

Al Oliver signed with the Pirates as a 17-year-old and made his big-league debut four years later. He finished second in the rookie of the year voting in 1969, posting a .285 average, 17 home runs and 70 RBIs, and he would become a productive player who could get on base, score runs and hit for a high average throughout an 18-year career, with 10 spent in Pittsburgh (1968-77). The emergence of future Hall of Famer Willie Stargell forced Oliver to move from first base to the outfield, and he responded with three All-Star selections while helping the Pirates become one of the premier teams in the National League in the 1970s. After Alou was traded, he became a key member of the “Lumber Company” teams in the early part of the decade, although he didn’t hit more than 20 home runs in any season with Pittsburgh. His best campaign was 1974, when he batted .321 with 198 hits, 85 RBIs and a career-high 96 runs. Oliver was on a Pirates team that won five division titles in six years and beat the Orioles in the 1971 World Series and was a part of the first all-minority starting lineup in major league history. He totaled eight runs, 18 hits, three homers and 14 RBIs in 23 playoff games.

Oliver played his final season in Pittsburgh in left field, allowing the next name on this list to take over in center. He batted .296 with 689 runs, 1,490 hits, 276 doubles, 56 triples, 135 home runs, 717 RBIs and 2,283 total bases in 1,302 games before he joined the Rangers as part of a four-team deal after the 1977 season. Oliver earned two All-Star selections each with Texas and Montreal, finished tied for third in the MVP voting with the Expos in 1982, and played for four other teams before he retired in 1985. He ended his career with a .303 average, 2,743 hits and 1,326 RBIs in 2,368 games, with several media members making a Hall of Fame case based on his career. Since retiring, Oliver has published two autobiographies and worked as a spiritual and motivational speaker.

Omar Moreno is a Panamanian speedster who earned the nickname “Antelope” and stole nearly 500 bases in a 12-year major league career. After a brief call-up to the Pirates in 1975, he started torturing opposing pitchers and catchers with six straight seasons with at least 30 steals, including leading the league in back-to-back years. Moreno had his best season at the plate in 1979, when he batted .282, led the N. L. with 77 stolen bases and set career highs with 110 runs, 196 hits and 69 RBIs. During the playoffs, he had seven runs, 14 hits and three RBIs in 10 games, rapping 11 hits and scoring the final run in the World Series victory over the Orioles. The following year, Moreno led the league with 13 triples and swiped 96 bases to finish second. Over the next two years, his numbers stayed consistent with an average of around .240, plus high steal and run totals. Moreno signed with the Astros but lasted just half a season before he was traded to the Yankees. He retired after spending 1986 with the Braves, returned to Panama and worked with underprivileged children, including running his own foundation and working as the nation’s Secretary of Sport.

Andy Van Slyke was drafted in the first round by the Cardinals in 1979 and, after four seasons on St. Louis’ major league roster, he was traded to Pittsburgh on April Fool’s Day 1987. He quickly established himself as a force on both offense and defense, earning three All-Star selections, five gold gloves and two silver sluggers during his eight seasons with the Pirates (1987-94). “Slick” had a solid season in 1988, batting .288 with 101 runs, 30 stolen bases, a league-leading 15 triples and career-best totals of 25 home runs and 100 runs batted in. He finished fourth in the MVP race for a second time in 1992, setting career highs with a 324 average, 103 runs, 199 hits and 42 doubles, leading the league in the last two categories. The Pirates outfield of Bonds, Van Slyke and Bonilla was arguably the best in the game, and the trio led Pittsburgh to three straight division titles in the early 1990s. Van Slyke appeared in 20 postseason contests, totaling seven runs, 17 hits, six doubles, one home run and nine runs batted in. He finished his time in Pittsburgh with a .283 average, 598 runs, 1,108 hits, 203 doubles, 67 triples, 117 homers, 564 RBIs, 134 steals and 1,796 total bases in 1,057 games. Van Slyke split his final season between the Orioles and Phillies in 1995, coached with the Tigers and Mariners and works with a prison ministry program.

5. Clarence “Ginger” Beaumont – He spent his career as a speedy leadoff hitter but started off as a catcher in the minor leagues. Beaumont joined the Pirates in 1899 and did something as a rookie that has never been equaled in the major leagues, going 6-for-6 with six runs scored. After a sophomore slump in 1900 where he “only” hit .279, his average jumped back over .300 in 1901 and stayed there for the next five seasons. Beaumont led the league with a .357 average and 193 hits in 1902 and batted .341 with league-leading totals of 137 runs, 209 hits and 272 total bases the following year to help Pittsburgh win the pennant. He was the first batter in the first modern World Series played after the 1903 season, and he had six runs, nine hits, two RBIs and two stolen bases in eight games, but the Pirates fell to the Boston Americans (later Red Sox).

Beaumont batted .301 and led the league for a third straight year with 185 hits in 1904, but knee issues were beginning to surface. He was traded to the Boston Doves (later Braves) after the 1906 season and led the league with 187 hits the following year, but his production soon diminished. Beaumont finished his eight-year Pirates career (1899-1906) ranked eighth in franchise history with a .321 average to go with 757 runs, 1,292 hits, 127 doubles, 57 triples, 31 home runs, 421 RBIs, 200 steals and 1,626 total bases in 989 games. He was released after spending the 1910 season with the Cubs and, after one year in the minor leagues in Minnesota, his baseball career was over. Beaumont ran a farm in Wisconsin and served as a county supervisor after his playing career. He suffered multiple strokes and passed away in 1956 at age 79.

4. Bill Virdon – He was a former Yankees prospect who was traded to the Cardinals, where he won the Rookie of the Year Award in 1955. After a monthlong slump to start the following season, Virdon was on the move again to Pittsburgh, where he would spend the rest of his 12-year career (1956-65 and ’68). He was known as one of the best center fielders in the game, winning three fielding titles and a gold glove during his Pirates tenure, while also becoming a solid and consistent hitter. Virdon batted .334 after the trade to finish second in the batting title, his only full season over the .300 mark. He also had 150 or more hits four times in his career and led the league with 10 triples in his gold glove season in 1962.

“The Quail” was also one of the fastest players in the game, helping him to be quite successful on bunt attempts. He was one of the key pieces on the surprising team that won the World Series in 1960, totaling two runs, seven hits and five RBIs in the upset of the Yankees. The team never came close to that success again and Virdon initially retired in 1965. Following two seasons as a minor league manager in the Mets organization, he was a coach for the Pirates in 1968 and appeared in six games as a player after several players had to miss time due to military obligations. Virdon managed in Puerto Rico for a year and took over the Pirates in 1972, leading them to a division title. He also managed the Yankees, Astros and Expos, retiring in 1984 after amassing a 995-921 record and two playoff appearances in 13 seasons. After his managerial career, he was a coach and minor league instructor for 17 years and passed away in 2021 at age 90.

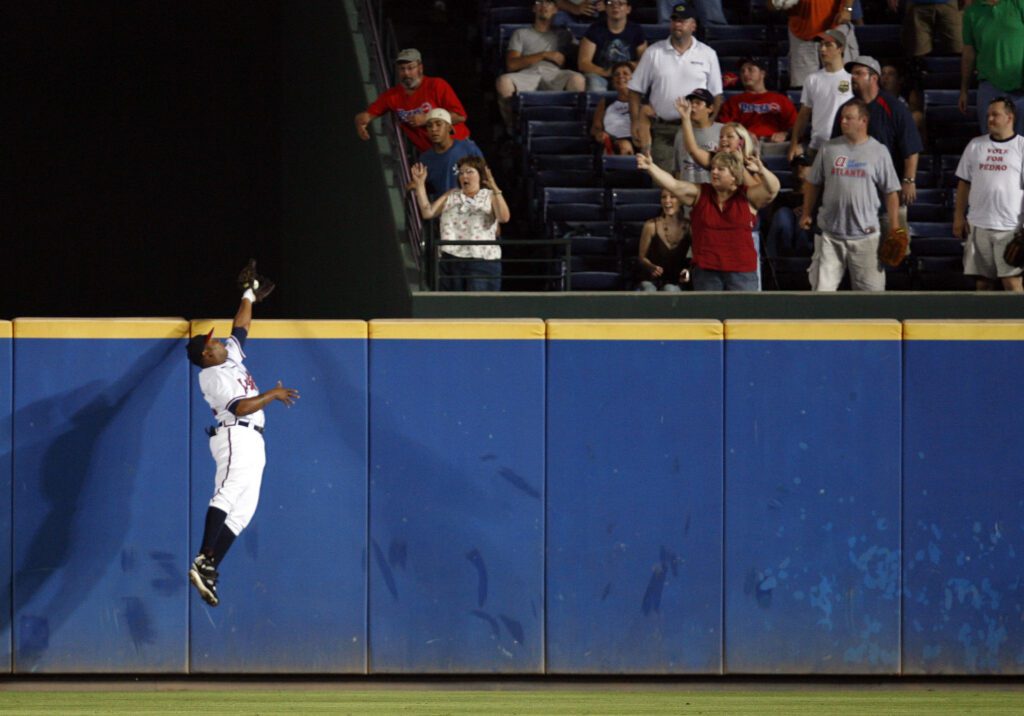

3. Andrew McCutchen – He was selected by the Pirates in the first round of the 2005 draft and played in the MLB All-Star Futures Game three years later before joining Pittsburgh in 2009. McCutchen earned Rookie of the Year consideration and became a consistent performer over his 11 seasons in the Steel City (2009-17 and 23-24). He avoided the sophomore slump, batting .285 with 94 runs and a career-high 33 stolen bases. McCutchen made his first of five straight All-Star teams in 2011 after driving in 89 runs, and he finished third in the MVP voting the following year, posting career-high totals of a .327 average, 107 runs, 194 hits, 31 home runs and 96 runs batted in. Although his numbers were not quite as good as the previous season (.317-21-84, 97 runs, 185 hits), McCutchen was named National League MVP in 2013. He followed that up with top-five finishes in each of the next two years, leading the league with a .410 on-base percentage in 2014.

In addition to his MVP, McCutchen collected some other hardware in Pittsburgh, including a Wilson Defensive Player of the Year Award in 2012, a gold glove in 2013, four silver sluggers and the 2015 Roberto Clemente Award. He was traded to the Giants before the 2018 season and spent time with the Yankees, Phillies and Brewers before returning to the Pirates as a free agent in 2023 to play at the designated hitter spot. Heading into the current season, McCutchen ranks third in franchise history in strikeouts (1,138), fourth in home runs (215), seventh in doubles (311), ninth in RBIs (768) and total bases (2,607) and tenth in games (1,458) to go with a .287 average, 869 runs, 1,563 hits and 182 stolen bases. McCutchen is known for his signature dreadlocks, proposing to his girlfriend on the Ellen DeGeneres Show in 2013 and being involved with several charitable organizations in the Pittsburgh area.

2. Max Carey – He was born with the last name Carnarius and was the son of a soldier in the German state of Prussia. The last name Carey came about when he was playing as a shortstop for a minor league team, and he wanted to keep his eligibility while he was still playing for Concordia College. When he found out he could make good money in baseball, he quit his education to become a Lutheran minister and played his first games with the Pirates. Carey became a productive and consistent player during his 17 seasons in Pittsburgh (1910-26), batting better than .300 six times and leading the league in triples twice and stolen bases 10 times. Worried about her son’s injury potential during stolen base attempts, his mother made him a sliding pad, which he later patented. Carey also was the first player to use flip-down sunglasses (which were patented by the team’s player-manager Fred Clarke).

“Scoops” had four straight seasons from 1922-25 in which he registered at least 100 runs, 175 hits and 45 stolen bases, leading the league in the last category each year. Overall, he had 10 seasons with at least 40 steals (reaching 50 six times), nine with 150 or more hits, eight with at least 10 triples (leading the league twice), six with 50 or more RBIs and five with at least 100 runs (he also led the league with 99 in 1913). Carey had a memorable game in July 1922, when he reached base nine times in an extra-inning marathon. He was a star in the 1925 World Series, helping the Pirates defeat the defending champion Washington Nationals. Carey had six runs, 11 hits, four doubles, three stolen bases and two RBIs in the series and had four hits against future Hall of Famer Walter Johnson in Game 7.

The end of Carey’s time in Pittsburgh came the following season. Clarke was now a vice president and part-owner of the club and sat on the bench during games. He gave his input for on-field decisions, which bothered some players, especially Carey, who called the team together to ban him from his usual spot in the dugout. In what was “later known as the “ABC Affair” (after Adams, Bigbee and Carey, who led the “mutiny” attempt), the team gave Clarke a vote of confidence and the three players responsible were let go by the team). Carey was claimed off waivers and spent the rest of this career with the Brooklyn Robins (later Dodgers).

Carey finished his Pirates career as the franchise’s all-time leader in stolen bases (688), and he ranks second in walks (918), fourth in games (2,178) and runs (1,414), tied for fourth in hits (2,416), fifth in doubles (375), and sixth in triples (148) and total bases (3,288) to go with a .287 average, 67 home runs and 721 runs batted in. He came back to the Pirates as a coach for two seasons and spent two more as Dodgers manager, leading Brooklyn to a 146-161 record. Although he suffered heavy losses in the Florida real estate market during the Great Depression, Carey stayed afloat through jobs in baseball that included running an instructional school, playing on an international travelling team, managing in the minor leagues and with the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, and writing a book on baseball strategy and tactics. Carey was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in 1961, fought for increased pensions for retired players and passed away in 1976 at age 86.

1. Lloyd Waner – His emergence allowed the Pirates to succeed even after Carey was waived in 1926. Waner was born in Oklahoma a year before the territory became the 46th state. The younger of two baseball-playing brothers, he got a teaching degree then followed his big brother, Paul, to San Francisco to play for Seals, a powerhouse in the Pacific Coast League. When Paul went east, the Pirates purchased Lloyd’s contract as well and, after a year in the minors, the brothers played together in Pittsburgh. Waner converted from second base to the outfield, playing next to his brother in center field for 14 of his 17 seasons (1927-41 and 44-45). Lloyd was a slap hitter who produced 160 or more hits nine times and reached the 200-hit mark in four of his first five seasons, including a league-leading 214 in 1931. The only time he missed was 1930, when he missed three months after having surgery to remove his appendix.

“Little Poison” was one of the few Pirates who had success in the 1927 World Series. Despite his team getting swept by the Yankees, he batted .400 (6-for-15) with five runs scored. Waner batted .300 or better 10 times over his first 12 seasons, scored more than 100 runs three times (including a league-best 133 as a rookie) and led the N. L. with 20 triples in 1929. He was also excellent on defense, winning three fielding titles, leading the league in putouts three times and both assists and double plays twice each. Waner batted .313 and earned his only All-Star selection in 1938, but he was helpless as the Pirates fell apart and lost a 6½-game lead over the final month of the season. Both brothers were reserves in 1940 and were left Pittsburgh, with Paul being sold to the Dodgers after the season and Lloyd being traded to the Braves after appearing in just three games in 1941.

After a season in which he also played with the Reds, Waner played one year with the Phillies and missed all of 1943 while working in an aircraft plant during World War II. He joined his older brother on the Dodgers the following season but was released and returned to the Pirates in June, spending one more season with Pittsburgh before retiring in 1945. Waner ranks sixth in franchise history in hits (2,317), seventh in runs (1,151) and total bases (2,895), eighth in games (1,803), ninth in triples (114) and tenth in average (.319) to go with 269 triples, 27 home run and 577 runs batted in. Despite all those statistics, his most impressive total is 167, which is the number of times he struck out with the Pirates, a rate of once every 44.9 at-bats. He was a scout for Pittsburgh for four years, then went west and was a field clerk for the Oklahoma City government. Waner was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in 1967 and passed away in 1982 at age 76.

Right Fielders

Honorable Mentions – Owen “Chief” Wilson became one of the better players of the Deadball Era thanks to his dependability as well as the power in his bat and his throwing arm. The Texas native signed with the Pirates in 1908 and was given his nickname not because he was a Native American but because he looked like a chief of the Texas Rangers (the police force, not the yet-to-exist baseball team). Wilson couldn’t hit in his rookie season but was kept in the lineup for his defense. He improved his offensive game significantly over the next few years, batting .300 with 12 home runs and a league-high 107 RBIs in 1911. The following year, he matched his batting average, set career highs with 80 runs and 175 hits, and posted a major league record 36 triples that will most likely never fall. Wilson was traded to the Cardinals in 1914, finishing his six-year Pirates career (1908-13) with a .274 average, 393 runs, 915 hits, 109 doubles, 94 triples, 44 home runs, 426 RBIs and 1,344 total bases in 899 games and added two runs, four hits and an RBI in the 1909 World Series victory. His skills quickly diminished over the next three seasons and his baseball career ended in the minor leagues in Texas in 1917. Wilson stayed out of the spotlight after his retirement and died while working on his ranch in 1954 at age 70.

Johnny Barrett got his start in the Red Sox organization but got sold to the Pirates due to the number of young, talented outfielders in Boston. He made his debut with Pittsburgh in 1942 and turned into a star while many ball players were in the military or working in factories or shipyards during World War II. Barrett had his best season in 1944, when he batted .269 with 99 runs, 153 hits and 83 RBIs and led the league with 19 triples and 28 stolen bases. The following year, he stole 25 more, scored 97 runs and hit a career-best 15 home runs. Barrett was traded to the Braves in 1946 and tore cartilage in his right knee, which required surgery. Boston sent him to the minors with San Diego, but he refused to report at first, instead challenging the move, saying he didn’t get a fair shot with the Braves. After three seasons, he received no offers, retiring for a year before finishing his career in 1951. Following his retirement, Barrett ran a liquor store and was the superintendent of the Essex County Training School until his death in 1974 at age 58.

Orlando Merced was a Puerto Rican native who was good friends with the sons of Pirates legend Roberto Clemente. When one of the boys was signed by Pittsburgh in 1985, Merced was at the house and got signed as well. He joined the Pirates for a brief callup in 1990 and finished as the Rookie of the Year runner-up the following season after posting a .275-10-50 stat line as a first baseman. Merced had two hits in the NLCS that year, one of which was a leadoff home run in Game 3 against future Hall of Famer John Smoltz. He fell off a bit in 1992 and the Pirates fell to the Braves again in the NLCS, but he was a solid run producer for the rest of his tenure. Merced was traded to Toronto in 1997, finishing his seven-year tenure in Pittsburgh (1990-96) with a .283 average, 396 runs, 739 hits, 146 doubles, 65 homers, 394 RBIs and 1,118 total bases in 776 games. He played for six teams over his final six seasons, retiring after spending 2003 with the Astros. Merced played two more seasons in his native country, coached in Mexico, Puerto Rico and in the minors with the Pirates and Reds organizations.

Gregory Polanco was a native of the Dominican Republic who signed with the Pirates in 2009, played in the MLB All-Star Futures Game four years later and made his big-league debut in 2014. Although he was never selected as an All-Star, he had several solid years. He set career highs in 2015 with 83 runs, 152 hits and 27 stolen bases and followed that with 22 home runs and a personal-best 86 runs batted in. After a solid year in 2018, Polanco had shoulder surgery the following season and a bout of COVID-19 in 2020. His average dropped to .208 the next year, and he was released in August. “El Coffee” finished the 2021 season in the minors with the Blue Jays and has not returned to the majors since a two-year stint in Japan. He totaled 399 runs, 696 hits, 156 doubles, 96 home runs, 362 RBIs and 1,178 total bases in 823 games over eight seasons with Pittsburgh (2014-21).

5. Hazen “Kiki” Cuyler got his nickname as a shortstop in the minor leagues when teammates would shout out the first part of his last name on fly balls and fans would imitate the call. Known for his speed and throwing arm, he began his baseball career as a pitcher while working in a Buick factory in Michigan. Cuyler signed with the Pirates in 1921 and had brief call-ups in each of the next three years before making the roster full-time in 1924. With regular playing time at all three outfield spots, he showed his worth, hitting at least .320 with 30 steals three times and leading the league in runs scored two straight years. Cuyler finished as the MVP runner-up in 1925 after batting .357 with 220 hits, 102 RBIs, 41 stolen bases, a career-high 18 home runs, league-leading totals of 144 runs and 26 triples and a franchise-record 369 total bases. He helped Pittsburgh defeat Washington in the World Series, totaling three runs, seven hits, and six RBIs in seven games and hitting a go-ahead home run in Game 2. The following year, Cuyler held out but had another stellar season with league-best totals of 113 runs and 35 steals. However, his time in Pittsburgh was beginning to unravel after his benching and subsequent participation in the “ABC Affair” (can anyone say mutiny?).

In 1927, Cuyler missed time with torn ankle ligaments after a slide, moved in the field and in the batting order upon his return and was fined after not sliding to break up a double play. The actions, combined with his previous holdout, led to a benching that annoyed fans and confused the press, especially when he didn’t play against the Yankees in the World Series. Cuyler was traded to the Cubs after the season and went on to post similar numbers to his best seasons with the Pirates. During his seven seasons in Pittsburgh (1921-27), he batted .336 with 415 runs, 680 hits, 115 doubles, 65 triples, 38 home runs, 312 RBIs, 130 steals and 1,039 total bases in 525 games. Cuyler also spent time with the Reds and Dodgers, retiring after a season as the game’s oldest player in 1938. He spent 11 seasons as a major and minor league coach, died at age 51 from a blood clot in his leg after suffering a heart attack in 1950 and was voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veteran’s Committee in 1968.

4. Patsy Donovan – The man known for his character and consistency was born in Ireland, and his family emigrated to Massachusetts when he was three years old. Donovan worked in the cotton mill as a youth, but baseball would be his way out. He bounced around the National League and American Association for a few years before he was traded to the Pirates in 1892. Donovan was a slap hitter known for his speed. He stole at least 30 bases in each of his eight years in Pittsburgh (1892-99), and he had more than 150 hits seven times, and batted better than .300 with at least 100 runs scored five times each. His best season of 1894 was arguably the game’s greatest in terms of offensive production around the league. That year, Donovan batted .303 with 175 hits, 41 steals and set career highs with 147 runs and 76 RBIs.

Donovan also had two stints as a player-manager with the Pirates with little success on a bad team. He was relieved of his duties at the end of the 1899 season in favor of left fielder Fred Clarke, then was traded to St. Louis, finishing his time in Pittsburgh with a .307 average, 842 runs, 1,286 hits, 122 doubles, 55 triples, 426 RBIs, 312 stolen bases (fourth in franchise history) and 1,557 total bases in 982 games. Donovan led the league with 45 steals in 1900, and he also played with Washington and Brooklyn, retiring in 1907. He had some success managing the Cardinals in the early part of the 20th century, but most of his other skipper jobs ended in disappointment. After a two-year stint in Boston, he stayed with the Red Sox as a scout and is credited with being the man who convinced the team to acquire a young pitcher named Babe Ruth. Donovan managed several at several stops in the minor leagues and was a longtime scout for the Yankees. The former coach of future president George H. W. Bush passed away on Christmas Day 1953 at age 88.

3. Dave Parker – He was born in Mississippi and his family moved to Cincinnati, where he would spend his summers as a teenager working as a vendor at Crosley Field. A knee injury in his senior year of high school not only cost him a chance to play college football but also caused his draft stock in baseball to drop (the Pirates took him in the 14th round in 1970). Three years later, he was playing with Pittsburgh in a platoon and, after missing nearly half of the following season, he began to show flashes of brilliance in 1975, finishing third in the MVP voting after posting a .308-25-101 stat line and leading the league with a .541slugging percentage. The campaign was the beginning of a five-year stretch in which he batted .300 or better and had at least 160 hits and 80 RBIs each season, hit at least 20 home runs and stole more than 15 bases four times each and scored at least 100 runs on three occasions (including another third-place MVP finish in 1977).

With Pittsburgh, “Cobra” was an outspoken team leader who was a four-time All-Star, a three-time gold glove winner and a two-time batting champion. His best season came in 1978, when he won the MVP Award after leading the league with a .334 average, a .585 slugging percentage and 340 total bases to go with 194 hits, 30 home runs and 117 runs batted in. Although he was bothered by a sore left knee the following year, he was named the MVP of the All-Star Game after making two incredible throws to cut down runners and was instrumental in the Pirates claiming the World Series title thanks to a pair of game-winning hits against the Orioles. Before the season began, Parker had signed a five-year extension with the Pirates. Although the value was never disclosed, he was thought to be baseball’s first million-dollar player, although much of the money was deferred over the next decade. Parker performed capably in the first two seasons of his new deal, but not good enough for Pittsburgh fans, who booed and occasionally threw things at him in the field. His later career was marred by knee, Achilles and weight issues and, despite a solid season in 1983, he was not brought back, ending his Pirates’ career ranked sixth in franchise history in home runs (166) and eighth in doubles (296) to go with a .305 average, 728 runs, 1,479 hits, 62 triples, 758 RBIs, 123 stolen bases and 2,397 total bases in 1,301 games.

Parker returned to his hometown with the Reds, earning two All-Star selections and two silver sluggers, finishing as the MVP runner-up in 1985 after leading the league with 42 doubles, 125 RBIs and 350 total bases while also winning the first-ever All-Star Home Run Derby. Unfortunately, the season was overshadowed by his testimony in the Pittsburgh Drug Trials, during which he admitted he used cocaine for nearly four years. Parker, like the other players involved, were granted immunity but faced a one-year suspension before a deal was reached to have a percentage of their salaries taken for drug abuse programs, submit to drug testing for the rest of their careers, participate in antidrug programs and contribute 200 hours of community service. Parker played two seasons with the Athletics (winning a second championship in 1989), was named an All-Star for the final time with the Brewers in 1990 and split his final season between the Angels and Blue Jays, winning two Designated Hitter of the Year Awards. Following his playing career, he had coaching stints with the Angels and Cardinals, ran several Popeye’s restaurants in the Cincinnati area, and started a foundation to combat Parkinson’s disease, which Parker was diagnosed with in 2012. Although he has borderline Hall of Fame statistics, his drug use has caused the writers to keep him out and push his candidacy to one of the other committees.

2. Paul Waner – Paul, like his younger brother, Lloyd, went to school in Oklahoma to become a teacher, but chose baseball as a career path instead. He started as a pitcher but developed a sore arm during a minor league stop in San Francisco and was moved to the outfield, where he stayed for the rest of his career. Waner was three years older than his brother, and he made sure the two played together, first with the Seals and then for 14 years with the Pirates. Without Lloyd in his first year in Pittsburgh, Paul batted .336 with 180 hits and led the league with 22 triples. The Waner brothers were together in 1927, with Paul earning the MVP Award after leading the league with a .380 average (third best in team history), 237 hits, 18 triples, 131 RBIs and 342 total bases while leading the Pirates to the pennant. He batted .333 (5-for-15) with three runs batted in against the Yankees in the World Series.

During that season, the brothers got their nicknames. In a series in Brooklyn, a loud fan was talking about the “Big Person” (Paul) and “Little Person” (Lloyd) who were making life difficult for the home team only, thanks to his Brooklyn Italian accent, “Person” sounded like “Poison”. Paul certainly was “Big Poison” to the rest of the National League during his 15 seasons in Pittsburgh (1926-40), earning four All-Star selections, winning three batting titles, finishing in the top 10 of the MVP voting six times (including a runner-up finish in 1934, batting .300 or better 13 times (five over .350), scoring more than 100 runs nine times, smacking 200 or more hits eight times, driving in at least 80 runs on six occasions and leading the league in doubles twice, including 62 in 1932, which ranks fifth in major league history.

Waner continued to perform, and the Pirates stayed near the top of the standings. In 1938, Pittsburgh was in first place by 3½ games with two weeks left when a tropical storm hit the East Coast, canceling four games. The Pirates then dropped a pair to the Cubs as Chicago blew past them to the pennant. Waner’s final years in Pittsburgh were marred by injury and alcohol use, and the club released him after the 1940 season. He is the all-time franchise leader in doubles (558), and he ranks second in batting average (.340), runs (1,493), triples (187), third in hits (2,868) and walks (909), fourth in total bases (4,127), fifth in RBIs (1,177) and sixth in games (2,159). He also hit 109 home runs, won four fielding titles and led the league in putouts four times and double plays twice. Waner played with the Braves and Dodgers (in Boston, he was reunited with his brother for a brief time and had his 3,000th career hit against his longtime team in 1942), and he ended his career by appearing in one game with the Yankees in 1945. Following his playing days, he was a hitting coach for several franchise and owned a batting cage in the Pittsburgh area. Waner was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1952 and passed away due to complications from emphysema at age 62 in 1965, two years before his brother was inducted.

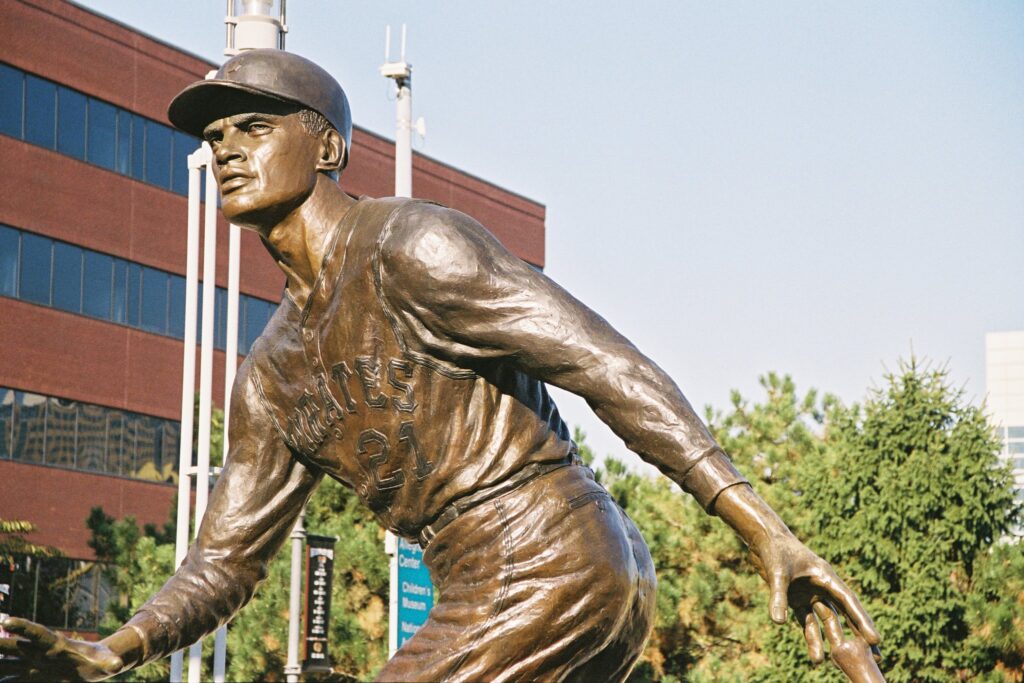

1. Roberto Clemente – He was arguably the best of the dozens of Latin American players who arrived in the United States after the integration of Major League Baseball. The Puerto Rico native impressed in his country’s winter league and was signed by the Dodgers for a $5,000 salary and a $10,000 bonus in 1954. The rule of the day (known as the “bonus baby” rule) stated that any young player signed for more than $4,000 had to spend at least two years on the major league roster or they could be lost to an offseason draft. The Dodgers kept him with their minor league affiliate in Montreal the entire season and later admitted they only signed Clemente to keep him away from the rival Giants. Brooklyn tried to work out a deal with Pittsburgh, who held the first pick in the draft thanks to having the league’s worst record. Although a deal was reached for the Pirates to draft another Montreal player (a minor league team was only allowed to lose one each offseason), a dispute from Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley caused Pirates general manager Branch Rickey (who formerly held that position in Brooklyn) to go back on his word and take Clemente.

Pittsburgh’s newest acquisition was decent at the plate in his rookie season but was stellar in the field, leading the league in assists for the first of six times in his career. Although he was progressing as a hitter, Clemente faced back issues in his early years that limited his power. His condition improved during an offseason military commitment with the U. S. Marine Reserves, but he missed the start of the 1959 season with an elbow injury sustained while making a diving catch. Clemente broke through the following year, batting .314 with 179 hits, 16 home runs and 94 runs batted in and earning berths in both major league All-Star Games. He continued his play in the World Series, batting .310 with nine hits and three RBIs against the Yankees, getting a hit in all seven games to help the Pirates win their first title in 35 years. Despite his complaints of injuries and ailments that, like many Latin players of the era, got him labeled as “lazy” or a “hypochondriac,” Clemente became a star during the decade, winning four batting titles, finished in the top 10 of the MVP voting seven times and smacking 200 or more hits four times (leading the league twice). He won his first batting title with a .351 average in 1961 and won his first of 12 straight gold gloves. His best season was 1966, when he won the MVP Award with a .317 average and career highs with 29 home runs and 119 RBIs to go with 105 runs, 202 hits and 342 total bases, and he finished third the following year.

Clemente continued his fantastic play when the 1970s began, and Pittsburgh won three straight division titles. Although the Pirates lost to the Reds in the NLCS in 1970 and ’72, they won their fourth championship in between. After dispatching the Giants in the NLCS, the Pirates faced the American League powerhouse Orioles in the World Series. Clemente made the Fall Classic his own personal showcase, batting .414 with three runs, 12 hits, two homers and four RBIs, earning MVP honors in the seven-game victory. He overcame an intestinal virus and strained tendons in both heels to smack a double against the Mets on September 30 for hit number 3,000.

As he had done many times before, Clemente returned to Puerto Rico to play winter ball following the 1972 season. After an Amateur tournament, the city of Managua, Nicaragua, was hit by a massive earthquake. Clemente organized an effort to raise money and get food and medicine to those hit by the disaster. On New Year’s Eve, he boarded a flight that was bringing supplies, but the plane had issues almost immediately after takeoff. The tried to return to the San Juan airport but crashed into the Atlantic Ocean about a mile off the coast. All five people on board, including Clemente (age 38), had perished.

Clemente is the franchise’s all-time leader in hits (3,000) and total bases (4,492), and he is tied for first in games (2,433), second in strikeouts (1,230) and third in runs (1,416), doubles (166), home runs (240) and RBIs (1,305) to go with a .317 average. Throughout his 18-year career (1955-72), the 15-time All-Star batted over .300 13 times, reached double-digit triples nine times, drove in at least 80 runs on seven occasions, produced more than 300 total bases four times and totaled more than 100 runs and 20 homers three times each. In addition to his six assist titles, he led the league in double plays by a right fielder three times and putouts twice. Following the tragedy, the Baseball Hall of Fame made an exception to its five-year retirement rule, and Clemente was inducted in 1973. In addition, Major League Baseball changed the name of the award given to a player for his accomplishments on and off the field to honor the Latin legend.

Upcoming Stories

Pittsburgh Pirates Catchers and Managers

Pittsburgh Pirates First and Third Basemen

Pittsburgh Pirates Second Basemen and Shortstops

Pittsburgh Pirates Outfielders

Pittsburgh Pirates Pitchers – coming soon

Previous Series

A look back at the Philadelphia Phillies

Philadelphia Phillies Catchers and Managers

Philadelphia Phillies First and Third Basemen

Philadelphia Phillies Second Basemen and Shortstops

Philadelphia Phillies Outfielders

Philadelphia Phillies Pitchers

A look back at the Oakland Athletics

Oakland Athletics Catchers and Managers

Oakland Athletics First and Third Basemen

Oakland Athletics Second Basemen and Shortstops

Oakland Athletics Outfielders and Designated Hitters

Oakland Athletics Pitchers

A look back at the New York Yankees

New York Yankees Catchers and Managers

New York Yankees First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

New York Yankees Second Basemen and Shortstops

New York Yankees Outfielders

New York Yankees Pitchers

A look back at the New York Mets

New York Mets Catchers and Managers

New York Mets First and Third Basemen

New York Mets Second Basemen and Shortstops

New York Mets Outfielders

New York Mets Pitchers

A look back at the Minnesota Twins

Minnesota Twins Catchers and Managers

Minnesota Twins First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Minnesota Twins Second Basemen and Shortstops

Minnesota Twins Outfielders

Minnesota Twins Pitchers

A look back at the Milwaukee Brewers

Milwaukee Brewers Catchers and Managers

Milwaukee Brewers First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Milwaukee Brewers Second Basemen and Shortstops

Milwaukee Brewers Outfielders

Milwaukee Brewers Pitchers

A look back at the Miami Marlins

Miami Marlins Catchers and Managers

Miami Marlins First and Third Basemen

Miami Marlins Second Basemen and Shortstops

Miami Marlins Outfielders

Miami Marlins Pitchers

A look back at the Los Angeles Dodgers

Los Angeles Dodgers Catchers and Managers

Los Angeles Dodgers First and Third Basemen

Los Angeles Dodgers Second Basemen and Shortstops

Los Angeles Dodgers Outfielders

Los Angeles Dodgers Pitchers

A look back at the Los Angeles Angels

Los Angeles Angels Catchers and Managers

Los Angeles Angels First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Los Angeles Angels Second Basemen and Shortstops

Los Angeles Angels Outfielders

Los Angeles Angels Pitchers

A look back at the Kansas City Royals

Kansas City Royals Catchers and Managers

Kansas City Royals First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Kansas City Royals Second Basemen and Shortstops

Kansas City Royals Outfielders

Kansas City Royals Pitchers

A look back at the Houston Astros

Houston Astros Catchers and Managers

Houston Astros First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Houston Astros Second Basemen and Shortstops

Houston Astros Outfielders

Houston Astros Pitchers

A look back at the Detroit Tigers

Detroit Tigers Catchers and Managers

Detroit Tigers First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Detroit Tigers Second Basemen and Shortstops

Detroit Tigers Outfielders

Detroit Tigers Pitchers

A look back at the Colorado Rockies

Colorado Rockies Catchers and Managers

Colorado Rockies First and Third Basemen

Colorado Rockies Second Basemen and Shortstops

Colorado Rockies Outfielders

Colorado Rockies Pitchers

A look back at the Cleveland Guardians

Cleveland Guardians Catchers and Managers

Cleveland Guardians First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Cleveland Guardians Second Basemen and Shortstops

Cleveland Guardians Outfielders

Cleveland Guardians Pitchers

A look back at the Cincinnati Reds

Cincinnati Reds Catchers and Managers

Cincinnati Reds First and Third Basemen

Cincinnati Reds Second Basemen and Shortstops

Cincinnati Reds Outfielders

Cincinnati Reds Pitchers

A look back at the Chicago White Sox

Chicago White Sox Catchers and Managers

Chicago White Sox First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Chicago White Sox Second Basemen and Shortstops

Chicago White Sox Outfielders

Chicago White Sox Pitchers

A look back at the Chicago Cubs

Chicago Cubs Catchers and Managers

Chicago Cubs First and Third Basemen

Chicago Cubs Second Basemen and Shortstops

Chicago Cubs Outfielders

Chicago Cubs Pitchers

A look back at the Boston Red Sox

Boston Red Sox Catchers and Managers

Boston Red Sox First and Third Basemen

Boston Red Sox Second Basemen and Shortstops

Boston Red Sox Outfielders and Designated Hitters

Boston Red Sox Pitchers

A look back at the Baltimore Orioles

Baltimore Orioles Catchers and Managers

Baltimore Orioles First and Third Basemen

Baltimore Orioles Second Basemen and Shortstops

Baltimore Orioles Outfielders and Designated Hitters

Baltimore Orioles Pitchers

A look back at the Atlanta Braves

Atlanta Braves Catchers and Managers

Atlanta Braves First and Third Basemen

Atlanta Braves Second Basemen and Shortstops

Atlanta Braves Outfielders

Atlanta Braves Pitchers

A look back at the Arizona Diamondbacks

Arizona Diamondbacks Catchers and Managers

Arizona Diamondbacks First and Third Basemen

Arizona Diamondbacks Second Basemen and Shortstops

Arizona Diamondbacks Outfielders

Arizona Diamondbacks Pitchers