By Kevin Rakas

This is the fifth and final article in a series that looks at the five best players at each position for the St. Louis Cardinals. In this installment are right- and left-handed starters as well as relief pitchers.

The list of the best pitchers in St. Louis Cardinals features several workhorses who spent their best years with the team. St. Louis features three Hall of Fame right-handed starters, including one of the most dominating hurlers of the modern era, several underrated lefties and talented closers who were effective at holding late-inning leads.

The Best Pitchers in St. Louis Cardinals History

Right-Handed Starters

Honorable Mentions – Bob Caruthers was frail as a child but used baseball to get in shape. He became one of the better pitchers in the early days of the American Association and was a solid hitter as an outfielder when he wasn’t on the mound. After a solid rookie season, Caruthers took his game to the next level in 1885, leading the league with a 40-13 record and a 2.07 earned run average to go with 53 complete games, six shutouts and 190 strikeouts in 482 1/3 innings. After earning the nickname “Parisian Bob” for negotiating his next contract by trans-Atlantic cable while he was vacationing in France, he won 30 games the following year and 29 in 1887, when he also put up his best campaign as a hitter, setting career highs with a .357 average, 102 runs, eight home runs, 73 RBIs and 49 stolen bases. Caruthers finished his five-year run with the Browns (1884-87 and ’92) ranked sixth in franchise history in complete games (151) and 11th in wins (108-48) to go with a 2.75 ERA, 151 complete games out of 152 starts, 10 shutouts and 509 strikeouts in 1,395 innings. He also was a three-time participant in the World’s Series, going 7-6, completing all 14 starts and striking out 47 batters in 123 innings. Caruthers pitched with Brooklyn for four years before returning to St. Louis for one season in the National League. After playing a few more years in the minor leagues, he was an umpire in the early 1900s, despite being visibly sick later in life. He passed away in 1911 at age 47.

Caruthers and Dave Foutz became a formidable duo during their four-year stint together with the Browns (1884-87). Like Caruthers, Foutz played in the field when he wasn’t pitching, often in the outfield or at first base. As a pitcher, he quickly came into his own, using a stellar side-arm curveball to post a 33-14 record for the pennant-winning club. His best season occurred the following year, when he led the American Association with a 41-16 record and a 2.11 earned run average, and his win total, along with 57 starts, 55 complete games, 11 shutouts, 283 strikeouts and 504 innings, were all the second-best single season marks in team history. “Scissors” finished his run with the Browns tied for third in franchise history in ERA (2.67), fourth in complete games (156) and ninth in wins (114-48) to go with 16 shutouts and 619 strikeouts in 1,457 2/3 innings. He appeared in the World’s Series three times, going 3-6, completing all nine of his starts and striking out 27 batters in 70 innings. As a batter, Foutz hit .296 with 204 runs, 353 hits and 201 RBIs in 302 games. After the team lost in 1887, he was traded to Brooklyn, where he spent the final nine seasons of his major league career, including a four-year run as manager that produced a 264-257 record. Foutz retired as a player following the 1896 season and pondered whether to become a full-time manager or umpire. Unfortunately, the answer was neither, as he suffered a winter-long bout of pneumonia, followed by an acute asthma attack that claimed his life in early 1897 at just 40 years old.

Charles “Silver” King was the son of German immigrants (original surname Koenig) who started his major league career with the National League’s Kansas City Cowboys in 1886. He joined the Browns, winning 32 games while teaming with Caruthers and Foutz to bring St. Louis a third straight pennant. When the others were traded away to Brooklyn, King took over as ace and went 32-12 in 1887. He had a fantastic season the following year, striking out 258 batters, setting team records (and leading the league) with a 45-20 record, 64 starts and complete games, and 584 2/3 innings, and topping the A. A. with a 1.63 earned run average, which ranks second in team history. Known for his temper and his whitish-blond hair, King went 35-16 in 1889 but held out and feuded several times with owner Chris von der Ahe. He went to the Players League the following year and became a journeyman, playing for five teams over his final six seasons and also sitting out two years. King ranks fifth in team history in complete games (154), sixth in ERA (2.70) and tenth in wins (112-48) to go with 161 starts, 10 shutouts and 574 strikeouts in 1,432 2/3 innings. He went 2-6 in the World’s Series, completing eight of nine starts and striking out 33 batters in 66 innings. King saw his career basically end in Washington after a line drive broke his pitching arm in 1896. He operated a contracting business in St. Louis and passed away in 1938 at age 57.

The run of successful St. Louis pitchers in the late 1800s continued with Jack Stivetts. His parents were German immigrants (original surname Stibitz) who settled in Pennsylvania coal country, but he found that baseball would be his ticket out of the mines. Stivetts get his big break pitching against the Browns in an 1889 exhibition game and getting signed by the American Association club after the game. He went 12-7 in 26 games in his first year and led the league with a 2.25 earned run average. “Happy Jack” was solid in each of the next two seasons, going 27-21 and striking out a team-record 289 batters the following year and ending his St. Louis career with a 33-22 record and a league-leading 259 strikeouts in 440 innings in 1891. In his three years with the Browns, Stivetts went 72-50 with a 3.01 ERA, 122 starts, 99 complete games, eight shutouts and 691 strikeouts in 1,051 innings. He signed with the Boston Beaneaters (later Braves), spent seven years with the club and threw the franchise’s first no-hitter in 1892. Stivetts was traded back to the Browns (then under new ownership), but was sent to the lowly Cleveland Spiders, and he was released in June 1899, his career at an end. He played semipro ball for a decade and worked as a carpenter in a coal mine. Stivetts passed away when he fell down a flight of stairs and suffered a heart attack in 1930 at age 62.

The Cardinals franchise was fairly inept for the first quarter of the 20th century, but Grover Alexander helped to change that. The longtime Phillies and Cubs star won three pitching Triple Crowns with Philadelphia from 1915-17. He was traded to St. Louis in June 1926, and he went 9-7 to help the Cardinals clinch their first pennant. Alexander won both of his starts against the Yankees in the World Series, but it was a relief appearance that will be the most remembered moment. St. Louis had a 3-2 lead with two outs in the seventh inning, but New York had the bases loaded. Alexander (who was rumored to be either drunk or hung over at the time) was called out of the bullpen and struck out future Hall of Famer Tony Lazzeri, then held the Yankees scoreless the rest of the way to get the save and give the Cardinals their first championship. “Old Pete” went 21-10 the following year and posted 16 wins as a 41-year-old in 1928. However, he went 0-1 as the Yankees won the World Series this time. He was traded back to Philadelphia for one final season in 1930, ending his four-year Cardinals tenure (1926-29) with a 55-34 record, a 3.08 earned run average, 59 complete games, five shutouts and seven saves in 792 innings. Alexander dealt with alcoholism for the remainder of his life, only getting sober long enough to attend the Baseball Hall of Fame ceremony after he was inducted in 1939. He passed away from cardiac arrest in 1950 at age 63.

Paul “Daffy” Dean was the son of a sharecropper who moved from Arkansas to Oklahoma picking cotton. He and his more famous (and much more vocal) older brother played semipro ball in San Antonio, and he was signed by the Cardinals in 1930. The quiet but more serious brother finally joined the Cardinals after four years, going 19-11 and throwing a no-hitter against the Dodgers in September. Dean (who hated his press-given nickname “Daffy”) was equally dominant against the Tigers in the World Series. Each of the brothers won a pair games for the “Gashouse Gang,” and Paul allowed just two runs and struck out 11 in his two complete games. After winning 19 games once again in 1935, he came into the following season in poor shape following one of his many holdouts. Dean was struggling thanks to postseason barnstorming and suffered an arm injury in early June. He pitched sparingly for the rest of the year and the injury was diagnosed as torn cartilage in his shoulder, which would require surgery. Dean appeared in just 57 games over the final six years of his career with the Cardinals, Giants and Browns. He ended his six-year St. Louis tenure (1934-39) with a 46-30 record, a 3.74 earned run average, 42 complete games, eight shutouts and 351 strikeouts in 669 innings. Dean spent 1942 as a guard at an aircraft plant near Dallas and ran a barrel-stave mill with his father-in-law following his playing days. He was a manager of an Army camp baseball team in California during World War II and played in the minor leagues while operating a restaurant in Arkansas. In later years, Dean had his name and likeness used in the “Pride of St. Louis,” a story about his family (especially his older brother), ran minor league and college teams in Texas, and managed several service stations. He passed away after suffering a heart attack in 1981 at age 68.

Mort Cooper is another Cardinals star who played alongside his brother (catcher Walker Cooper). He originally was a catcher until he injured his hand off a batted foul tip in grade school and switched positions with his brother on the mound. Cooper survived a near-fatal automobile accident while he was in the minors and pitched for 11 years in the major leagues, including eight with St. Louis (1938-45). He won at least 20 games in three straight seasons, helping the team win the pennant each time. With no Cy Young Award at the time, Cooper did what few pitchers had accomplished, win the MVP Award in 1942 after leading the league with a 22-7 record, a 1.78 earned run average and 10 shutouts for the Cardinals, who set a franchise mark with 106 wins. Although he lost his only decision against the Yankees, his team won its first of two titles in three years. He again led the league in wins with a 21-8 mark (including back-to-back one-hitters) the following year and went 22-7 with a league-best seven shutouts in 1944. The Cooper brothers held out before the next season, and the ordeal ended with Mort being traded to the Braves and Walker being sold to the Giants while he was still in the Navy during World War II. The two-time All-Star finished third in franchise history with 28 shutouts to go with a 105-50 record, a 2.77 ERA, 195 complete games and 758 strikeouts in 1,480 1/3 innings with St. Louis. He earned All-Star nods in his first two years with Boston but had three elbow surgeries which shortened his career considerably. Cooper also was an alcoholic who squandered his money and made a mess of his personal life. He was arrested for writing bad checks, had a messy public divorce and owned several failed business ventures (especially a tavern). Cooper suffered from liver problems and passed away from a combination of cirrhosis, pneumonia, diabetes and a staph infection in 1958 at age 45.

Chris Carpenter overcame so many physical obstacles to play 15 major league seasons. The New Hampshire native was scouted by several NHL teams but chose baseball instead. He was a first-round pick of the Blue Jays in 1993 and made his debut with Toronto four years later. Carpenter was inconsistent during his six years with the Blue Jays and endured elbow and shoulder surgeries while with Toronto. He signed with the Cardinals in 2003 but didn’t pitch at all that season after another surgery to remove scar tissue from his right shoulder. Carpenter considered retirement but while rehabbing, he noticed the movement on his pitches had returned. He had three straight stellar seasons, with St. Louis, winning 15 games twice and earning the National League Cy Young Award in between after going 21-5 with a 2.83 earned run average, 213 strikeouts and a league-high seven complete games.

Despite back spasms and bursitis, Carpenter pitched in the playoffs the following year, going 3-1 and throwing eight shutout innings in his only appearance against the Tigers to help his team win the World Series. He appeared in just five games in the next two seasons after undergoing two more surgeries (bone spurs in the elbow in 2007 and a compressed nerve in his shoulder the following year). Carpenter finished as the runner-up for the Cy Young Award and was named Comeback Player of the Year in 2009 after going 17-4 and leading the league with a 2.24 ERA. He stayed off the disabled list the following two seasons and was fantastic during the 2011 playoffs, going 4-0, including a shutout in the clinching game of the Division Series and two wins against the Rangers in the World Series to win his second championship. The three-time All-Star dealt with a nerve problem the following year that required a sixth surgery, but when he experienced numbness in his pitching hand afterward, he decided to retire, finishing his nine-year Cardinals career (2004-12) ranked fourth in franchise history in strikeouts (1,085) to go with a 95-44 record, a 3.07 ERA, 1,348 1/3 innings, 21 complete games and 10 shutouts. He is now a mental skills coach for minor league pitchers in the Angels’ system.

5B Bob Forsch – He was a reliable and underrated pitcher who never earned an All-Star selection in his 15 seasons with the Cardinals (1974-88). The younger of two brothers who were both selected in the 1968 draft, Forsch was struggling as an infielder and converted to pitcher while in the minor leagues and made his first start for St. Louis in 1974. He was steady thorough the years, reaching double digits in wins 10 times including seven in a row from 1977-83. Although Forsch was never an All-Star, he had his best season in the first year of his streak, going 20-7 with a 3.48 earned run average and eight complete games. The following year, he threw his first of two no-hitters beating the Phillies in April (the other came against the Expos in 1983). Forsch appeared in three World Series with the Cardinals and won a title in 1982 despite losing both of his starts to the Brewers. He we 3-4 overall in 12 playoff appearances, including five starts.

Forsch was traded to the Astros late in the 1988 season, finishing his time with the Cardinals ranked third in games started (401), fourth in wins (163-127) and innings (2,658 2/3), fifth in games pitched (455) and strikeouts (1,079) and ninth in shutouts (19) to go with a 3.67 ERA and 67 complete games. In his post-playing days, the two-time silver slugger wrote a book, worked as an instructor at Cardinals fantasy camps and was a minor league pitching coach with the Reds. Forsch passed away in 2011 at age 61, less than a week after he threw out the first pitch before Game 7 of the World Series. He was inducted into the Cardinals Hall of Fame in 2015.

5A Bill Doak – He relied on a curveball and a now-illegal pitch which give him his “Spittin’ Bill” nickname during a 16-year career, 13 spent in St. Louis (1913-24 and ’29). Doak started his career with the Reds and was a Sunday school teacher before going out to the ballpark. After the Cardinals purchased his contract, he went 19-6 with seven shutouts and led the league with a 1.72 earned run average in 1914. Doak reached double figures in wins eight times, including 1920, when he posted career bests with a 20-12 record and 20 complete games to go with a 2.53 ERA and five shutouts. The following year, he again won the ERA title at 2.59 and won 15 games. Doak also pitched three near-no-hitters that were lost because of mental lapses. He lost two of them when he failed to cover first base on grounders to the right side and a third when he didn’t come off the mound to field a bunt.

Doak was known for two moments that occurred off the field following the 1919 season. He went to Rawlings with drawings of an enlarged glove that improved fielding capabilities, which the company used and marketed as the “Premier Players’ Glove.” Doak also lobbied for players who already threw spitballs to be allowed to use the pitch even after it was outlawed in 1920. He was traded to the Brooklyn Robins (later Dodgers) in 1924 and won 10 straight games during a failed pennant run. After taking two years off to sell real estate, Doak spent two more years with the Dodgers and made three appearances with the Cardinals in 1929, finishing his time in St. Louis ranked second in franchise history in shutouts (30), fifth in games started (320), sixth in wins (144-136) and innings (2,387), eighth in games pitched (376) and ninth in complete games (144) and strikeouts (938) to go with a 2.93 earned run average. He ran a candy store, coached youth and high school baseball and was a golf professional in Central Florida until he passed away in 1954 at age 63.

4. Adam Wainwright – Wainwright grew up a Braves fan and was selected by his hometown team in the first round in 2000. Three years later, he was sent to the Cardinals in the trade the featured outfielder J. D. Drew heading to Atlanta. After a brief callup in St. Louis, he joined the team as a bullpen arm in 2006, earning four postseason saves to help the team win the World Series. He famously struck out future teammate Carlos Beltran to end the NLCS and help the Cardinals beat the Mets. The following year, Wainwright moved to the starting rotation and made just four relief appearances the rest of his career. He posted a double-digit win total 12 times during his career and led the league twice (19 in both 2009 and ’13). In between, he was the Cy Young runner-up after winning a career-best 20 games and set a career-high with a 2.42 earned run average in 2010, missed the following season after undergoing Tommy John surgery and returned to go 14-13 in 2012.

In addition to his win total in 2013, Wainwright posted a 2.94 ERA and a personal-best 219 strikeouts, led the league with 241 2/3 innings, five complete games and two shutouts to finish second in the Cy Young voting. He was third the following year after going 20-9 with a 2.38 ERA and an N. L.-best three shutouts. Wainwright earned three All-Star selections, two gold gloves and a silver slugger in 2017 after hitting two of his 10 career home runs. He was a part of nine playoff appearances, going 4-5 with a 2.83 ERA and 123 strikeouts in 114 1/3 innings over 29 appearances, including 16 starts. Wainwright missed most of the 2015 (ruptured Achilles tendon) and 2018 seasons (right elbow inflammation) but continued to pitch well until his final of 23 seasons (2005-10 and 11-23). He ranks second in franchise history in starts (411) and strikeouts (2,202) and third in wins (200-128), games pitched (478) and innings (2,668 1/3) to go with a 3.53 ERA, 28 complete games and 11 shutouts, and he set a record by making 324 starts with catcher Yadier Molina. Wainwright has kept busy after his playing career by working as a color commentator with Fox Sports and releasing a country music album.

3. Jesse Haines – The Ohio farm boy made a relief appearance with the Reds in 1918 and, after spending one year in the minor leagues, he joined the Cardinals as a 26-year-old and was the last player the team purchased before the advent of a massive farm system. Haines started off with a solid fastball and curveball but became one of the better pitchers in the league after developing a knuckleball. He posted a double-digit win total 11 times in his first 12 seasons and reached 20 on three occasions. Haines went 8-19 in 1924 but had his best individual moment, a no-hitter against the Braves in July that was the only one thrown by a Cardinals pitcher in Sportsman’s Park. His best season was 1927, when he set career highs with a 24-10 record, a 2.72 earned run average and 300 2/3 innings, and he led the league with 25 complete games and six shutouts.

Nicknamed “Pop” by his teammates because he played well into his 40s, Haines was the only player on the roster for the team’s first five pennants. He went 3-1 in six games, including four starts, and he was 2-0 with a shutout in Game 3 against the Yankees in the 1926 World Series. Haines missed the 1931 championship loss to the Philadelphia Athletics after suffering a right shoulder injury in September that led to a move to the bullpen and a downturn to his career that ended in 1937. He is the all-time franchise leader in appearances (554) and ranks second in wins (210-158), innings (3,203 2/3) and complete games (209), fourth in games started (387), tied for fifth in shutouts (23) and seventh in strikeouts (979) along with a 3.64 earned run average. Haines was a pitching coach with the Dodgers for one season then worked as a county auditor in Ohio for 28 years. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in 1970 and passed away after a long bout of cancer in 1978 at age 85.

2. Jay “Dizzy” Dean – He was the son of a sharecropper and regularly missed school to help his father pick cotton. Dean was discovered while pitching on a military base in Texas after joining the Army at age 16 (he told them he was 18), and he also earned his nickname during his three-year stay. He made one start at the end of the 1930 season and spent the following year in the minors before joining the Cardinals on a full-time basis. Dean led the league in strikeouts in each of his first four full seasons, going 18-15 with an N. L.-best four shutouts and 286 innings in 1932. He reached 20 wins and set a career high the following year before winning the MVP Award and earning his first of four straight All-Star selections in 1934 after leading the league with a 30-7 record (becoming the last pitcher to win that many in the National League), 195 strikeouts and seven shutouts. “Dizzy” and Paul Dean were instrumental in helping the Cardinals win the pennant and each of them won two games in the World Series against the Tigers. Dean was the colorful, talkative leader of the “Gashouse Gang,” a group of St. Louis players who played hard, talked a lot and had plenty of fun. However, he and his quiet brother were both temperamental and held out on a regular basis, with their act beginning to wear thin on teammates, opponents and fans.

Dean finished as the MVP runner-up in each of the next two years, leading the league with a 28-12 record, 190 strikeouts, 325 1/3 innings and 29 complete games in 1935, but the Cardinals fell short of the pennant. He won 24 games the following year while also leading the league with 315 innings, 28 complete games and 11 saves, and had 12 wins at the break in 1936 when his career took a downturn. Dean was hit in the foot by a line drive during the All-Star Game, breaking a toe. He changed his delivery to accommodate the injury and the pressure he put on his arm led to bursitis. Dean was traded to the Cubs the following season but won just 16 more games over the next four seasons, mostly as a spot starter. He finished his seven-year Cardinals career (1930 and 32-37) ranked third in franchise history in strikeouts (1,095), tied for fifth in shutouts (23), seventh in wins (134-75) and tenth in innings (1,737 1/3) and complete games (131) to go with a 2.99 ERA. Dean was a radio broadcaster for the Cardinals, Browns, Yankees and Braves, called games on television for ABC and CBS and had a movie made about his life. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1953 and passed away after suffering a heart attack in 1974 at age 64.

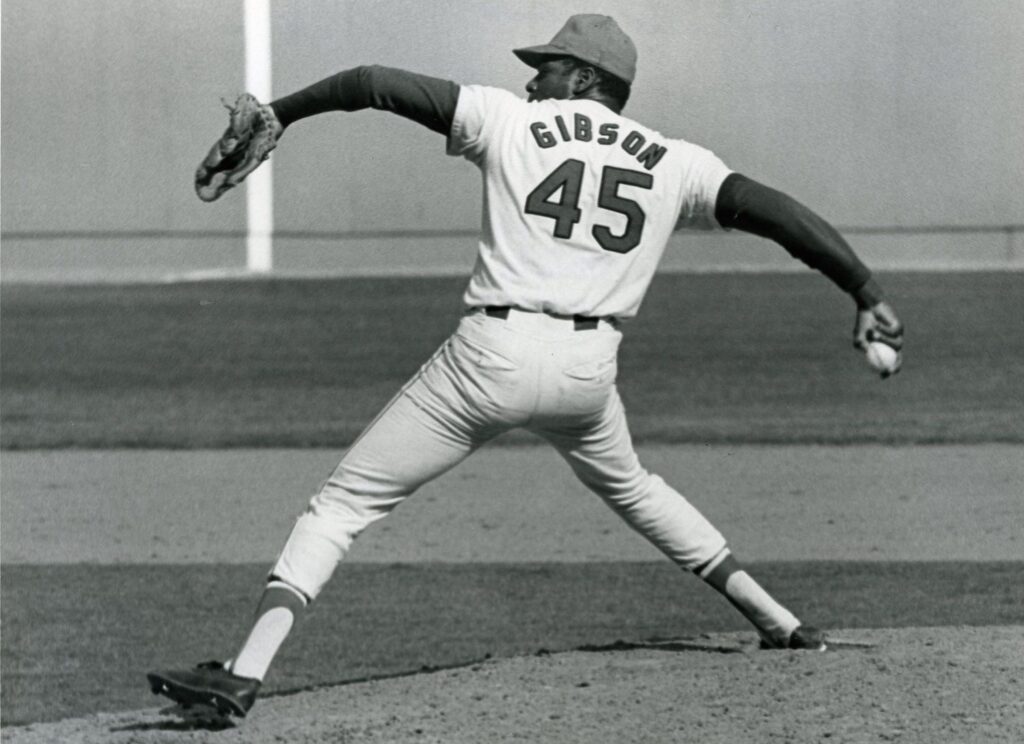

1. Bob Gibson – His father died before he was born, so his older brother mentored him and helped him get into Creighton University, where he set records in basketball and played baseball under Bill Fitch, who would later coach in the NBA. After not receiving any pro basketball offers, Gibson played with the Harlem Globetrotters but turned down a full-time offer to sign with the Cardinals in 1957. He made his debut in St. Louis two years later but struggled as a spot starter during his first two seasons, but things changed when manager Solly Hemus, who was known for being prejudiced against black players was replaced by Johnny Keane, who was the minor league manager that helped developed him. Gibson developed pinpoint control of two different fastballs as well as a stellar slider, and he became one of the most dominant pitchers in the game. He amassed double digit win totals in 14 straight seasons, including 20 or more five times. He also struck out at least 200 batters in a season nine times, including five in a row from 1962-66.

Although he was aloof and one of the most serious and intimidating players of his era, Gibson was instrumental in promoting race relations among his teammates. On the field, he won 19 games in 1964 and was named the MVP of the World Series after winning two games against the Yankees. Gibson posted at least 20 wins in each of the next two years and struck out 270 batters in 1965. He missed time in 1967 with a broken bone in his leg but returned in time to win another World Series MVP Award after going 3-0 against the Red Sox. The following season, Gibson posted one of the game’s all-time great campaigns, winning both the Cy Young and MVP awards after going 22-9, leading the league with 268 strikeouts and 13 shutouts while setting a post-World War I record with a 1.12 earned run average and led to the league lowering the height of the pitching mound. He won his first two starts of the World Series against the Tigers but lost Game 7 after holding giving up three runs in the seventh inning.

Gibson won 20 more games in 1969 and took home the Cy Young Award again the following year after striking out a career-best 274 batters and leading the league with a 23-7 record. Although that was the last time he reached the 20-win mark, he continued to pitch well, throwing his only no-hitter in August 1971 against the Pirates. Gibson won 19 games the following year, then tore cartilage in his knee in 1973 ending his team’s chances at another pennant. He spent his entire 17-year career with the Cardinals (1959-75) and retired as the all-time franchise leader in wins (251-174), starts (482), complete games (255), shutouts (56), innings (3,884 1/3) and strikeouts (3,117). He ranks second in appearances (528) and has a 2.91 ERA. Gibson was stellar in the postseason, going 7-2 with a 1.89 ERA, completing eight of nine starts with two shutouts and striking out 92 batters in 81 innings. The nine-time All-Star was also a fantastic fielder, earning nine straight gold gloves from 1965-73. “Hoot” was a broadcaster for baseball and basketball for more than two decades, was the chairman of a bank, owned a radio station and ran a restaurant near his alma mater for nearly a decade. Gibson was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1981 and later served as a coach with the Braves and Cardinals. He passed away due to pancreatic cancer in 2020 at age 84.

Left-Handed Starters

Honorable Mentions – Max Lanier broke his right arm as a child, and it didn’t reset properly. When he broke it again four years later after cranking an old car, he began to use his left hand while his right one was in a cast. Lanier signed with the Cardinals while he was still in high school and, after four seasons between the minors and semipro ball, he made his debut with St. Louis in 1938. Using a solid fastball and a sweeping curve, he became a two-time All-Star who reached double figures in wins six times. Lanier became a star on a team that won three straight pennants, going 13-8 in the 1942 regular season and winning a game in relief against the Yankees in the World Series. He followed with his two best seasons, posting a 15-7 mark and leading the league with a 1.90 earned run average in 1943 and going 17-12 with a 2.65 ERA and career-best totals of 15 complete games and five shutouts the next year. After a bout of appendicitis nearly ended his season, he returned to win Game 6 against the Browns and give the Cardinals another championship.

Lanier spent most of the 1945 season in the Army at the end of World War II and, after a holdout, he had a solid start the following year. However, the Cardinals were known for being stingy with paying their players and other leagues began to take notice. One of those was the Mexican League, whose president began to tantalize American players with huge contracts. Lanier went to Mexico to play but was suspended from the major leagues for five years. After leaving the league, he played in Cuba, Canada and for semipro teams in the U. S. before he was reinstated in 1949 once he filed a lawsuit, and he spent three more years with St. Louis. Lanier finished his 12-year run with the Cardinals (1938-46 and 49-51) with a 101-69 record, a 2.84 ERA, 764 strikeouts in 1,454 2/3 innings, 85 complete games and 20 shutouts (tied for seventh in franchise history. He played with the Giants and Browns before retiring in 1953. Lanier played two more years in the minor leagues, ran a restaurant and was a scout, instructor and manager for several major league teams. He passed away in 2007 at age 91.

Since expansion occurred in 1961, baseball has seen a shift in the usage of starting pitchers. In the early days of the game, rosters were small, and pitchers were expected to complete every game. Now, the complete-game shutout is a rare feat, and even more rare is a pitcher reaching double figures in the category. The last one to reach the mark was John Tudor, who did so with the Cardinals in their 1985 pennant-winning season. A Red Sox draft pick, he was traded to the Pirates and Cardinals in back-to-back years. After a 1-7 start in his first season in St. Louis, Tudor ran off 20 wins over his final 26 starts, finishing with career highs in every major category, including a 21-8 record, a 1.93 earned run average, 169 strikeouts in 275 innings and 14 complete games to go with his shutout total. The Cy Young runner-up went 1-1 against the Dodgers in the NLCS and won his first two starts in the World Series before falling to the Royals in Game 7. In his disappointment, he punched a cooling fan in the clubhouse and cut open his hand.

Tudor continued to put together solid seasons despite recurring shoulder stiffness that led to surgery in 1987 and undergoing a procedure on his knee the following year. After another losing effort in the World Series, the Cardinals traded him to the Dodgers late in the 1988 season. He made two playoff starts but underwent Tommy John surgery that cost him nearly all the next year. Tudor signed with the Cardinals for one final season in 1990, earning the Comeback Player of the Year Award and finishing his five-year tenure in St. Louis (1985-88 and ’90) with a 62-26 record, a 2.52 ERA (second in franchise history), 448 strikeouts in 881 2/3 innings, 22 complete games and 12 shutouts. In the postseason, he went 5-4 in nine starts, striking out 42 in 57 innings. Tudor played in a city league in Massachusetts at first base for two years and served as a minor league pitching coach and instructor for several major league organizations.

5. Theodore Breitenstein – He was the one bright spot on a bad Browns team at the end of the 19th century. Known for his sharp curve and pinpoint control, Breitenstein lost his parents when he was a teenager and made stoves while playing for the company’s baseball team. After spending a year with the Browns Reserves, a precursor to the minor league system, he joined the big-league club in its final season in the American Association in 1891. Breitenstein was used sparingly in relief but made his first career start at the end of the season and threw a no-hitter against Louisville. While he was talented in an era in which offense was king, he was also inconsistent at times, thanks to heavy drinking. Breitenstein led the league with a 3.18 earned run average in 1893, and he topped the N. L. with 447 1/3 innings the following year and led the Senior Circuit in complete games twice.

“Theo” was letting his habit get the better of him, leading to fines and suspensions, but he was still producing on the field, winning at least 18 games in four straight seasons, including a 27-23 mark in 1894. Meanwhile, the Browns couldn’t crack 60 wins during this time, with their star lefty earning 83 of his team’s 192 victories during that four-year span. Breitenstein was sold to the Reds in 1897 and put together four solid seasons on a much more competitive team but arm troubles eventually hurt his effectiveness and ended his major league career. He made three lackluster starts with the Cardinals in 1901, finishing his career in St. Louis ranked third in franchise history in complete games (198), seventh in innings (1,934 1/3) and eighth in games started (222) to go with a 94-125 record, a 4.28 ERA, six shutouts and 629 strikeouts. Breitenstein pitched for a decade in the minor leagues, throwing two more no-hitters, then worked as an umpire. He passed away due to heart failure in 1935 at age 65, just eight days after his wife.

4. Harry “Slim” Sallee – Nicknamed because of his thin frame (6-foot-3, 150 pounds for most of his career), the crafty, control-driven lefty came from rural Ohio to reach the major leagues in 1908. Sallee used a “cross-fire” delivery to fool batters and become one of the best pitchers in the National League despite being on one of the worst teams in the early 20th century. However, Sallee was never a fan of conditioning, and his alcohol consumption led to him being fined and suspended multiple times for leaving practices and disappearing for days at a time. After cleaning up his act, he posted double digit wins in six seasons, including five in a row from 1911-15. He won 19 games in 1913 and had a stellar season the following year with an 18-17 record, a 2.10 earned run average, 18 complete games and a league-leading six saves.

In 1916, Sallee finally grew tired of the losing and the poor attitudes around him and walked away until he was sold to the Giants, finishing his nine-year run with the Cardinals (1908-16) tied for third in franchise history in ERA (2.67), eighth in inning (1,905 1/3) and ninth in games started (213) to go with a 106-107 record, 123 complete games, 17 shutouts, 26 saves and 652 strikeouts. He won 18 games with the Giants in 1917 (breaking up a potential players’ strike by signing with New York) and posted a 21-7 record two years later for a Reds team that won the World Series following the infamous “Black Sox” scandal. Sallee finished his career with a second stint with the Giants in 1921 and, after one minor league season, returned to Ohio. He saved his earnings, so he was able to open several businesses, most of which were wiped out by a flood. Sallee managed the local team to a county championship in 1947 and passed away three years later from a heart attack at age 65.

3. Steve Carlton – Much like the previous two names on this list, Carlton spent parts of his career as a dominant pitcher on a bad team. He won 27 games and the Cy Young Award in 1972 with a Phillies team that won just 59 times that season. Before that, Carlton spent seven seasons with the Cardinals (1965-71), perfecting the slider that would make him one of the best pitchers in baseball. He earned three All-Star selections and made three postseason appearances with the Cardinals during their back-to-back pennant seasons. He lost his only start in 1967 despite giving up just an unearned run against the Red Sox in Game 5. Facing the Tigers the following year, Carlton struggled in two relief outings.

“Lefty” had his best season with St. Louis in 1969 when he went 17-11 with a 2.17 earned run average and 210 strikeouts, including a major-league record 19 against the Mets in September. After leading the league with 19 losses the following year, he went 20-9 with 18 complete games in 1970. However, Carlton held out the following year and was sent to the Philadelphia, where he won four Cy Young Awards, won at least 20 games five times (leading the league on four occasions) and leading the team to the World Series twice, including a dramatic win in 1980. He won his 300th game late in the 1983 season with the Phillies and spent time with four other teams before retiring in 1988. Carlton was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility in 1994.

2. Harry Brecheen – The Oklahoma farm boy spent eight years in the minor leagues but didn’t get to the majors until he developed a screwball to go with his fastball and curve. Brecheen made three relief appearances with the Cardinals and spent two more years in the minors thanks to the great depth of pitchers in St. Louis. When the team began losing hurlers during World War II, he returned in a spot starter role and made three appearances during a World Series loss to the Yankees. The following year, Brecheen went 16-5, beginning a run of six straight seasons with at least 14 wins. He was part of a formidable rotation with Cooper and Lanier and won Game 4 of the World Series against the crosstown rival Browns that was dubbed the Trolley Series. Known as “The Cat” for his quick reflexes and stellar fielding, Brecheen overcame an elbow injury to go 15-4 in 1945 and won 15 games the following year despite getting poor run support. He earned wins in each of his three appearances in the World Series against the Red Sox, including a shutout in Game 2 and a win in relief in the deciding seventh game.

Brecheen added a slider to his arsenal and went to the All-Star Game in each of the next two years, winning 16 games in 1947 and going 20-7 and leading the league with a 2.24 earned run average, 149 strikeouts and seven shutouts the following year. He won 14 games in 1949, but his elbow issues got worse, and he signed with the Browns for both the final season of his career and the team’s final year in St. Louis. Brecheen finished his 11-year run with the Cardinals (1940 and 43-52) ranked fourth in franchise history in shutouts (25), seventh in games started (224), eighth in wins (128-79) and ninth in innings (1,790 1/3) to go with a 2.91 ERA, 122 complete games and 857 strikeouts. After he retired, he stayed with the team and was the pitching coach of the relocated Baltimore Orioles for the next 14 years, helping the staff develop into an American League powerhouse. Brecheen passed away in 2004 at age 89.

1. Bill Sherdel – He spent three years in the minor leagues before signing with the Cardinals in 1917. Sherdel joined St. Louis the following year as a long reliever and spot start, posting a 2.71 earned run average despite finishing with a 6-12 record. He broke out in his first season as a full-time starter in 1922, going 17-13 and fooling hitters with “slowballs” (a combination of curves and changeups). Sherdel was sent back to the bullpen in 1924 but returned the following year to start a run of four straight years with at least 15 wins. He amassed 16 wins in 1926, including an eight-inning relief appearance against the Giants the clinched the pennant for the Cardinals. In the World Series against the powerful Yankees, he gave up just four earned runs in 17 innings but lost both starts.

“Wee Willie” won 17 games the following year, then had his best season in 1928, going 21-10 with a 2.86 ERA, a career-high 20 complete games and a league-leading five saves. Once again, he won the pennant clinching game but lost twice in the World Series, with the Yankees coming out on top this time. Sherdel was ineffective the following year and traded to the Braves midway through the following season. He returned to the Cardinals less than two years later, made three appearances and was released. Sherdel ended his 14-year run in St. Louis (1918-39 and ’32) ranked fourth in franchise history in appearances (465), fifth in wins (153-131) and innings (2,450 2/3), sixth in starts (243) and tied for seventh in complete games (145) to go with a 3.65 ERA, 11 shutouts, 779 strikeouts and 25 saves. The three-time fielding champion was a bartender and operated a local diner in Pennsylvania after his baseball career. He passed away from cerebral anoxia (lack of oxygen to the brain) in 1968 at age 72.

Unknown

George “Jumbo” McGinnis is one of the few mystery players in baseball history. Very little is known of his birth or upbringing, except that he was a glassblower before he turned to baseball. He joined the Browns in their inaugural season in the American Association in 1882 and won 77 games in his first three seasons. McGinnis got his nickname from his weight, which at 200 pounds, is not large by today’s standards but was at the time he played. Although St. Louis won pennants in his final two seasons, he did not pitch in the World’s Series either year. McGinnis was the odd man out in 1885 and was sold to Baltimore the following July. He finished his five seasons with the Browns (1882-86) tied for seventh in franchise history in complete games (145 in 153 starts) and earned run average (2.73) and tied for tenth in shutouts (18) to go with an 88-61 record and 474 strikeouts in 1,325 innings. Known as a finesse pitcher, McGinnis finished his major league career with Cincinnati in 1887, but the wear and tear on his arm (whichever one he used to pitch) became too much, and he finished his playing career after three more minor league seasons. He went back to glassblowing and filling in occasionally as an umpire. His primary job nearly cost him his eyesight and, after undergoing successful cataract surgery, he became a city inspector in St. Louis. McGinnis passed away from stomach cancer in 1934 at age 80.

Relief Pitchers

Honorable Mentions – Alpha “Al” Brazle was a hard-throwing strikeout pitcher during his semipro and minor league days. He signed with the Red Sox but was traded to the Cardinals in 1940 without pitching a game for Boston. Like many on the St. Louis staff, Brazle was used as a spot starter and long reliever early in his career, which began in 1943. He went 8-2 in 13 games but lost his only start against the Yankees in the World Series. The day after the final game, he was inducted into the Army, where he played baseball and saw combat in Germany and Austria during his two-year stint. “Cotton” (a nickname given because of his wiry, light blond hair) returned to his similar role with the Cardinals after World War II and ran off six double-digit winning campaigns in seven seasons. He lost in his only appearance in the 1946 World Series, but his current team beat his former team, the Red Sox. Brazle suffered several arm injuries, was converted to a full-time reliever in 1952 and led the league in saves in two straight seasons. He developed a knuckleball in 1954 but was released after the season. Brazle officially retired after a failed stint in the minors the following year and finished his 10-year run in St. Louis (1943 and 46-54) with a 97-64 record, a 3.31 earned run average, 442 appearances (sixth in franchise history), 59 saves (tied for ninth) and 554 strikeouts in 1,377 innings. The lefty became a building contractor and apartment manager and coached baseball in Florida after his playing career. He passed away due to a heart attack in 1973 at age 60.

Named after the famous aviator Charles Lindbergh, Lindy McDaniel was scouted by the Cardinals while he was still in high school. He Signed with St. Louis in 1955 and was immediately installed on the roster, spending his first few years between long relief and starting. McDaniel received a few spot starts later in the decade but was mostly used as a relief specialist, a role in which he excelled. He led the league in saves in two straight years, including 1960, when he went 12-4 with a 2.09 earned run average and 27 saves to earn his only All-Star selections (the league held two games at that time) and finishing third in the Cy Young race, becoming the first reliever to earn votes for the award. McDaniel was less affective in the next two years, and he was traded to the Cubs after the 1962 season. He finished his eight-year Cardinals tenure (1955-62) with a 66-54 record, a 3.88 ERA, 336 appearances (tenth in franchise history), 66 saves (tied for seventh) and 523 strikeouts in 884 2/3 innings. McDaniel led the league in saves in his first season with Chicago and pitched for 13 more years after the trade. He posed a career-best 29 saves with the Yankees in 1970 and had 174 over his 21 seasons. Following his 1975 retirement, McDaniel was a Christian minister and preacher in Texas until his death from COVID-19 in 2020 at age 84.

Al Hrabosky was an Oakland native who was drafted by the Cardinals in the first round in 1969 and made his major league debut the following. Although the team was not at the top of the standings throughout the 1970s, fans came to St. Louis to see him pitch. Known as “The Mad Hungarian” for his intimidating nature, Hrabosky would come into the game, turn and walk toward second base, talk to the ball while he was rubbing it, slam it into his glove before stomping back to the mound. After he grew a Fu Manchu mustache and beard, he looked even more fierce, and he was effective on the mound, earning Cy Young and MVP votes in two straight seasons. His best year was 1975, when he finished third in the Cy Young voting after going 13-3 with a 1.66 earned run average, a league-leading 22 saves and 82 strikeouts in 97 1/3 innings. Hrabosky was traded to the Royals, ending his eight-year tenure in St. Louis (1970-77) with a 40-20 record, a 2.93 ERA, 59 saves (tied for ninth in franchise history) and 385 strikeouts in 451 1/3 innings over 329 appearances. He retired after spending 1982 with the Braves and has been a color commentator for Cardinals games since 1985.

Ryan Franklin was a Mariners draft pick who earned a gold medal with Team USA during the 2000 Summer Olympics in Australia. He was inconsistent as a starter but found his place in the back of the bullpen after signing with the Cardinals in 2007. Following a year in middle relief, Franklin became the closer and was named an All-Star in 2009 thanks to a 1.92 earned run average and a career-best 38 saves. Despite earning 27 more saves the following year, his numbers declined, and he was released following the 2011 season and subsequently retired. In five years with St. Louis (2007-11), Franklin went 21-19 with a 3.52 ERA, 84 saves (sixth in franchise history) and 198 strikeouts in 312 1/3 innings. After three years away from the game, he returned to the Cardinals as a member of their baseball operations team.

5. Trevor Rosenthal – He was drafted by the Cardinals as a shortstop in 2009 but became a starting pitcher in the minors. Rosenthal never made a start in the major leagues, as coaches in St. Louis thought his blazing fastball would translate well to a late-inning relief role. After striking out 108 batters in 75 1/3 innings as a setup man in 2013 and posting four playoff saves during the team’s run to the World Series, he was installed as the closer the following year. Rosenthal had 45 saves in his first season in the role and a team record 48 in 2015 to earn his only All-Star selection. He fell off over the next two years before his 2017 season ended early due to a torn ulnar collateral ligament the required Tommy John surgery. Rosenthal finished his six-year stint in St. Louis (2012-17) with an 11-24 record a 2.99 earned run average, 121 saves (fifth in franchise history) and 435 strikeouts in 325 innings. After a year off, he split the next two seasons among four teams but hasn’t pitched since 2020 due to multiple injuries including thoracic outlet surgery and a torn labrum in his hip in 2021, hamstring and lat injuries in 2022 and another torn UCL in 2023.

4. Todd Worrell – He was a first-round pick by the Cardinals in 1982 and was used as a starter until he was called up to the St. Louis roster three years later. Worrell went 3-0 with five saves in 17 appearances down the stretch and was solid in the playoffs. He saved Game 1 of the World Series and was in line to get another in the potential clincher in Game 6 when umpire Don Denkinger ruled a Royals batter safe on a play in which he was covering first base. “The Call” ratted Worrell, and he gave up two runs, allowing Kansas City to win the title. He recovered the following year and used his overpowering fastball to win the Rookie of the Year and Rolaids Relief awards after posting a league-leading 36 saves, which was also a record among first-year players at the time.

Worrell notched 30 saves in each of the next two years, adding three more in the 1987 playoffs in which the Cardinals reached the World Series and earning his first All-Star selection the following year. He was attempting to tie the team’s saves record in a game in early September 1989 when he suffered a torn ulnar collateral ligament that required surgery. If that wasn’t bad enough, during his rehab, he tore his rotator cuff that led to another surgery and another year missed. Worrell came back in a setup role in 1992 but recorded three saves to take over the all-time franchise record. He signed with the Dodgers the following year, finishing his six-year Cardinals career (1985-89 and ’92) with a 33-33 record, a 2.56 earned run average, 129 saves (now third in franchise history), and 365 strikeouts in 425 2/3 innings over 348 games (ninth). Worrell had 127 saves (a team record at the time) and earned two All-Star selections with Los Angeles, including a league-leading 44 in 1996. He was a high school and independent league pitching coach and has been involved with the Fellowship of Christian Athletes organization.

3. Bruce Sutter – When surgery to repair a pinched nerve took away his fastball, he developed a dominating splitter that turned him into one of the most heralded relievers in the game. After five minor league seasons, Sutter made his debut with the Cubs in 1976, and he went on to earn All-Star selections in each of the next four years. His best season was 1979, when he won the Cy Young Award after tying a major league record with 37 saves. The Cubs traded Sutter to the division-rival Cardinals following the 1980 season, and he led the league in saves and finished in the top five of the Cy Young three times during his four-year run in St. Louis (1981-84).

Sutter was instrumental in the Cardinals’ championship run in 1982, earning three saves in the playoffs including two against the Brewers in the World Series. During his final season in St. Louis, he had a 1.54 earned run average, tied the single season saves record once again, this time with 45, and finished third in the Cy Young race. With the Cardinals, Sutter went 26-30 with a 2.72 ERA, 127 saves (fourth in franchise history) and 259 strikeouts in 396 2/3 innings. He signed with the Braves in 1985 but developed shoulder inflammation that required surgery and cost him a year and a half. He returned in 1988 but was not his usual self, despite earning his 300th career save. Sutter became the first pitcher who never started a game in the majors to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006. The four-time Rolaids Relief Award winner passed away in 2022 at age 69.

2. Lee Smith – The Cardinals have more than their fair share of intimidating relief pitchers and Smith is no exception. Like Sutter, he started his Career with the Cubs, earning two All-Star selections in eight seasons. After three years with the Red Sox, the 6-foot-6, 250-pound scowling hurler was traded to the Cardinals early in the 1990 season to help replace Worrell, and he soon became recognized as the league’s premier closer. Smith had a 2.10 earned run average and 27 saves after the trade and dominated the following year, finishing as the Cy Young runner-up and earning an All-Star selection after leading the league and setting a team record (since broken) with 47 saves. He reached 40 in each of his next three seasons with St. Louis and was named an All-Star two more times.

Smith was traded to the Yankees, finishing his four seasons in St. Louis (1990-93) as the team’s all-time leader with 160 (now second) to go with a 15-20 record, a 2.90 ERA and 246 strikeouts in 266 2/3 innings. The two-time Rolaids Relief Award winner played for five teams over his final five seasons and retired in 1998 as the all-time leader in saves with 478 over his 18-year career. Smith was a coach and scout for the Giants and was the pitching coach for the South African team in two World Baseball Classics. After failing to get voted in by the writers in 15 tries, he was finally elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Today’s Game Era Committee in 2018.

1. Jason Isringhausen – Although many relievers begin their careers as starters, few had expectations put on their shoulders the way he did. Although he was a late-round pick by the Mets, he improved greatly during his development to the point that he was part of “Generation K,” a trio of prospects that were supposed to take New York by storm in the late 1990s. However, injuries eventually took their toll. All three (Bill Pulsipher and Paul Wilson) had Tommy John surgery, and Isringhausen somehow had a 16-year career despite undergoing the procedure three times. He also had a bout of tuberculosis and broke his wrist after punching a trash can in the dugout. Eventually, Isringhausen was converted to the bullpen and traded to the Athletics during the 1999 season. He became a star closer after the deal, earning his first All-Star selection in 2000 and posting back-to-back 30-save seasons.

Isringhausen signed with the Cardinals in 2002 and became a major part of the team’s renaissance. He posted 30 or more saves five times in seven seasons (2002-08) and helped the team get to the NLCS three times and reach the World Series in 2004. That year, the closer led the league and tied a team record (since broken) with 47 saves, then added three more against the Astros in the NLCS. Unfortunately, the season ended with the Cardinals being swept by the Red Sox to win their first title in 86 years. Isringhausen earned his second and final All-Star selection after amassing 39 saves and posting a 2.14 earned run average in 2005, but he had hip surgeries in the next two offseasons. He sandwiched one solid season between two rough ones and ended his final season early due to elbow issues, finishing his time in St. Louis as the all-time franchise leader in saves (217) and ranking seventh in games pitched (401) to go with a 17-20 record, a 2.98 ERA and 373 strikeouts in 408 innings.

After a stint with the Rays, Isringhausen missed more than a year after undergoing Tommy John surgery. He returned to the Mets for one year in 2011, earning his 300th career save in August, and spent his final season with the Angels before retiring. Following his retirement, Isringhausen has stayed out of baseball except for a stint as the volunteer pitching coach with Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville. He dropped off the Hall of Fame ballot after not receiving a vote in 2018.

The next team to be featured will be the San Diego Padres.

Upcoming Stories

St. Louis Cardinals Catchers and Managers

St. Louis Cardinals First and Third Basemen

St. Louis Cardinals Second Basemen and Shortstops

St. Louis Cardinals Outfielders

St. Louis Cardinals Pitchers

Previous Series

A look back at the Pittsburgh Pirates

Pittsburgh Pirates Catchers and Managers

Pittsburgh Pirates First and Third Basemen

Pittsburgh Pirates Second Basemen and Shortstops

Pittsburgh Pirates Outfielders

Pittsburgh Pirates Pitchers

A look back at the Philadelphia Phillies

Philadelphia Phillies Catchers and Managers

Philadelphia Phillies First and Third Basemen

Philadelphia Phillies Second Basemen and Shortstops

Philadelphia Phillies Outfielders

Philadelphia Phillies Pitchers

A look back at the Oakland Athletics

Oakland Athletics Catchers and Managers

Oakland Athletics First and Third Basemen

Oakland Athletics Second Basemen and Shortstops

Oakland Athletics Outfielders and Designated Hitters

Oakland Athletics Pitchers

A look back at the New York Yankees

New York Yankees Catchers and Managers

New York Yankees First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

New York Yankees Second Basemen and Shortstops

New York Yankees Outfielders

New York Yankees Pitchers

A look back at the New York Mets

New York Mets Catchers and Managers

New York Mets First and Third Basemen

New York Mets Second Basemen and Shortstops

New York Mets Outfielders

New York Mets Pitchers

A look back at the Minnesota Twins

Minnesota Twins Catchers and Managers

Minnesota Twins First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Minnesota Twins Second Basemen and Shortstops

Minnesota Twins Outfielders

Minnesota Twins Pitchers

A look back at the Milwaukee Brewers

Milwaukee Brewers Catchers and Managers

Milwaukee Brewers First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Milwaukee Brewers Second Basemen and Shortstops

Milwaukee Brewers Outfielders

Milwaukee Brewers Pitchers

A look back at the Miami Marlins

Miami Marlins Catchers and Managers

Miami Marlins First and Third Basemen

Miami Marlins Second Basemen and Shortstops

Miami Marlins Outfielders

Miami Marlins Pitchers

A look back at the Los Angeles Dodgers

Los Angeles Dodgers Catchers and Managers

Los Angeles Dodgers First and Third Basemen

Los Angeles Dodgers Second Basemen and Shortstops

Los Angeles Dodgers Outfielders

Los Angeles Dodgers Pitchers

A look back at the Los Angeles Angels

Los Angeles Angels Catchers and Managers

Los Angeles Angels First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Los Angeles Angels Second Basemen and Shortstops

Los Angeles Angels Outfielders

Los Angeles Angels Pitchers

A look back at the Kansas City Royals

Kansas City Royals Catchers and Managers

Kansas City Royals First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Kansas City Royals Second Basemen and Shortstops

Kansas City Royals Outfielders

Kansas City Royals Pitchers

A look back at the Houston Astros

Houston Astros Catchers and Managers

Houston Astros First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Houston Astros Second Basemen and Shortstops

Houston Astros Outfielders

Houston Astros Pitchers

A look back at the Detroit Tigers

Detroit Tigers Catchers and Managers

Detroit Tigers First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Detroit Tigers Second Basemen and Shortstops

Detroit Tigers Outfielders

Detroit Tigers Pitchers

A look back at the Colorado Rockies

Colorado Rockies Catchers and Managers

Colorado Rockies First and Third Basemen

Colorado Rockies Second Basemen and Shortstops

Colorado Rockies Outfielders

Colorado Rockies Pitchers

A look back at the Cleveland Guardians

Cleveland Guardians Catchers and Managers

Cleveland Guardians First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Cleveland Guardians Second Basemen and Shortstops

Cleveland Guardians Outfielders

Cleveland Guardians Pitchers

A look back at the Cincinnati Reds

Cincinnati Reds Catchers and Managers

Cincinnati Reds First and Third Basemen

Cincinnati Reds Second Basemen and Shortstops

Cincinnati Reds Outfielders

Cincinnati Reds Pitchers

A look back at the Chicago White Sox

Chicago White Sox Catchers and Managers

Chicago White Sox First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Chicago White Sox Second Basemen and Shortstops

Chicago White Sox Outfielders

Chicago White Sox Pitchers

A look back at the Chicago Cubs

Chicago Cubs Catchers and Managers

Chicago Cubs First and Third Basemen

Chicago Cubs Second Basemen and Shortstops

Chicago Cubs Outfielders

Chicago Cubs Pitchers

A look back at the Boston Red Sox

Boston Red Sox Catchers and Managers

Boston Red Sox First and Third Basemen

Boston Red Sox Second Basemen and Shortstops

Boston Red Sox Outfielders and Designated Hitters

Boston Red Sox Pitchers

A look back at the Baltimore Orioles

Baltimore Orioles Catchers and Managers

Baltimore Orioles First and Third Basemen

Baltimore Orioles Second Basemen and Shortstops

Baltimore Orioles Outfielders and Designated Hitters

Baltimore Orioles Pitchers

A look back at the Atlanta Braves

Atlanta Braves Catchers and Managers

Atlanta Braves First and Third Basemen

Atlanta Braves Second Basemen and Shortstops

Atlanta Braves Outfielders

Atlanta Braves Pitchers

A look back at the Arizona Diamondbacks

Arizona Diamondbacks Catchers and Managers

Arizona Diamondbacks First and Third Basemen

Arizona Diamondbacks Second Basemen and Shortstops

Arizona Diamondbacks Outfielders

Arizona Diamondbacks Pitchers