This is the second article in a series that looks at the five best players at each position for the Oakland Athletics. In this installment are the first and third basemen.

Many of best teams in Athletics franchise history featured players that appear on these lists. The club can boast three of the best power-hitting first basemen in league history and several players on the other side of the infield who are solid contact hitters and fantastic fielders.

The Best First and Third Basemen in Oakland Athletics History

First Basemen

Honorable Mentions – John “Stuffy” McInnis was part of the “$100,000 infield” for Connie Mack during the 1910s and was a part of four pennant-winning and three championship teams in nine seasons (1909-17). He was a productive hitter who made great contact but earned his nickname for his defense. When he played as a youth, teammates and fans would yell, “That’s the stuff!” after he made a great play. McInnis began his career as a shortstop with the Athletics at age 18 in 1909 but replaced Harry Davis (a player further ahead on this list) at first base two years later. He didn’t play at all during Philadelphia’s 1910 World Series victory and suffered an injured wrist late in the following season, but he was put in to record the final out of the title victory.

Despite the team’s success, owner and manager Connie Mack began selling off players to save money. McInnis was the last member of the fabled infield on the roster in the middle of the decade, and he was traded to the Red Sox after refusing to take a pay cut. He finished his Athletics career batting .313 (ninth in franchise history) with 462 runs, 1,192 hits, 147 doubles, 13 home runs, 532 RBIs, 127 stolen bases and 1,478 total bases in 1,042 games. In addition to the Red Sox, he played for the Indians, Braves and Pirates before retiring in 1926. He had a one-year stint managing the Phillies and led college teams at Norwich, Cornell and Harvard before passing away in 1960 at age 69.

Vic Power – The Puerto Rican-born slugger began his career in 1954, the Athletics’ final season in Philadelphia, after being traded from the Yankees, becoming one of the first wo black players to suit up for the franchise. Power saw his career take off after the A’s moved to Kansas City, earning two straight All-Star selections and winning a gold glove. He had his best season in 1955, setting career highs with a .319 average and 19 home runs to go with 91 runs, 164 hits and 76 runs batted in. Power was traded to the Indians in 1958 and earned two more All-Star selections and six gold gloves over the next seven years spent with four teams. With the Athletics, he batted .290 with 655 hits, 100 doubles, 59 homers and 246 RBIs in 582 games. Power retired in 1965 and was a manager, scout and youth clinic instructor in his homeland. He passed away from cancer in 2005 at age 78.

Matt Olson was selected in the first round coming out of high school in Georgia in 2012 and made his debut with the Athletics four years later. He developed into one of the more productive hitters in the league, posting four seasons with at least 20 home runs and three with more than 80 RBIs in his six-year tenure in Oakland (2016-21). Olson missed time in 2019 after having surgery on his hand and struggled the following year, batting just .195 during the COVID-shortened season. However, he responded in 2021 by earning his first All-Star selection after posting a .271-39-111 stat line. Olson finished his time in the Bay Area with 323 runs, 517 hits, 101 doubles, 142 home runs, 373 RBIs and 1,046 total bases in 575 games. He appeared in nine postseason contests, amassing four runs, four hits, two homers and three RBIs.

The two-time gold glove recipient was part of the team’s fire sale before the 2022 season, and he was sent to the Braves with four young players coming to the Athletics. Olson hit 34 home runs and drove in 103 runs in his first year in Atlanta and went to another level in 2023, hitting a career-best .283 and leading the National League with 54 homers and 139 runs batted in while becoming an All-Star for the second time and winning his first silver slugger. In addition to his skills on the field, he works with the ReClif Center, a fitness and treatment facility for people on the autism spectrum.

5. Ferris Fain – The son of an alcoholic father who rode a horse that finished second in the 1912 Kentucky Derby, Fain spent six of his nine seasons with the Athletics (1947-52). He played baseball on a team with Yankees stars Joe DiMaggio, Red Ruffing and Joe Gordon while serving with the Army Air Force during World War II and soon after joined an A’s team that was struggling to stay relevant. Despite playing on some bad teams, Fain earned three All-Star selections and won two batting titles during his time with Philadelphia. He was aggressive at the plate, in the field and with his temper, which his frequent drinking did not help. Despite his talent, Fain was traded to the White Sox in 1953. He finished his Philadelphia tenure with a .297 average, 460 runs, 887 hits, 174 doubles, 35 home runs, 436 RBIs and 1,220 total bases in 844 games. Fain played with the Tigers and Indians in 1955, but chronic knee issues resulting in three surgeries ultimately ended his career. He passed away due to leukemia in 2001 at age 80.

4. Harry Davis – He attended a school for orphans in Philadelphia after his father died of typhoid and his mother was unable to provide for their four children. While he was there, Davis was given the nickname “Jasper,” took a liking to business and excelled at baseball. He bounced around the national league in the late 1890s and briefly retired to work for a railroad company before owner and manager Connie Mack recruited him to the Athletics. Davis was excellent in getting on base and producing runs, qualities he showed as the team’s starter over the next decade. He hit better than .300 and led the league in doubles three times each and topped the circuit in RBIs twice. However, he was recognized as one of the premier power hitters of the Dead Ball Era, leading the American League in home runs four straight years from 1904-07.

Davis’ totals declined over his final few seasons with Philadelphia, and he moved on in 1912 to manage Cleveland while also playing in two games. When the Naps struggled, he resigned and returned to the Athletics as a player-coach under Connie Mack, appearing in just 19 games over his final five seasons. Davis retired in 1917 after he was elected to the Philadelphia City Council but returned to the team to be a coach and scout until 1927. He ranks third in franchise history in doubles (319), fifth in triples (82) and stolen bases (223), sixth in hits (1,500), seventh in games (1,413) and ninth in runs (811) to go with a .279 average, 69 home runs, 761 RBIs and 2,190 total bases in 16 seasons (1901-11 and 13-17). Davis was a part of six pennant-winning teams and won three championships, totaling eight runs, 15 hits, five doubles and seven RBIs in 16 World Series games. He had several business ventures in the Philadelphia area and was a skilled trapshooter after his playing career. Davis passed away in 1947 at age 74 after having a stroke at his home.

3. Jason Giambi – Before joining the Athletics, he played on Team USA, which finished fourth at the 1992 Summer Olympics. Giambi spent time in his first few years at both corner infield and corner outfield positions before setting in at first base in 1998 and finding himself in batting in the heart of the Oakland order. In each of the next four years, he posted a .290-25-100 or better stat line, and he batted .315 with 33 home runs, 123 RBIs, 115 runs and a career-best 181 hits in 1999. The following year, Giambi won a hotly contested race for the MVP Award, edging out Frank Thomas, Alex Rodriguez and Carlos Delgado, who all had similar numbers to the .333-43-137 he posted. The Athletics’ star finished second in 2001 despite hitting 38 homers, driving in 120 runs and leading the league with 47 doubles, 129 walks, a .477 on-base percentage (also a team record) and a .660 slugging percentage.

When the A’s refused to put a no-trade clause into his contract, Giambi signed a seven-year, $120 million deal with the Yankees before the 2002 season. In order to meet with his new team’s requirements, he cut his long hair, shaved his facial hair and curtailed his wild ways, which included drinking, partying and riding custom-built motorcycles. Giambi continued his productive ways in his first five years with the team (other than parts of 2004 in which he suffered from an illness that turned out to be a tumor on his pituitary gland), but he was also under suspicion of using steroids during this time. He admitted to using them and the Yankees tried to void his contract before Players’ Union stepped up to protect him. A notoriously slow starter, Giambi left New York and signed back with Oakland in 2009, where he was released in August after hitting just .193 in 83 games. He also spent time with the Rockies and Indians before retiring in early 2015.

Giambi finished his eight-year Athletics career (1995-2001 and ’09) ranked eighth in franchise history with 198 home runs, and he also batted .300 with 640 runs, 1,100 hits, 241 doubles, 715 RBIs and 1,949 total bases in 1,036 games. He also appeared in the postseason twice with Oakland, totaling four runs, 10 hits, one homer and five RBIs in 10 games, but the A’s lost to the Yankees in the Division Series in 2000-01. Giambi hit 440 home runs and driving in 1,441 runs during a 20-year career and earned five All-Star selections (two with Oakland), won the Hutch Award in 2000 and the Comeback Player of the Year Award in 2005. Despite winning the 2002 All-Star Home Run Derby and appearing on the cover of five baseball video games, his name will be tainted due to his association with the BALCO steroid scandal and investigation during some of his most productive seasons.

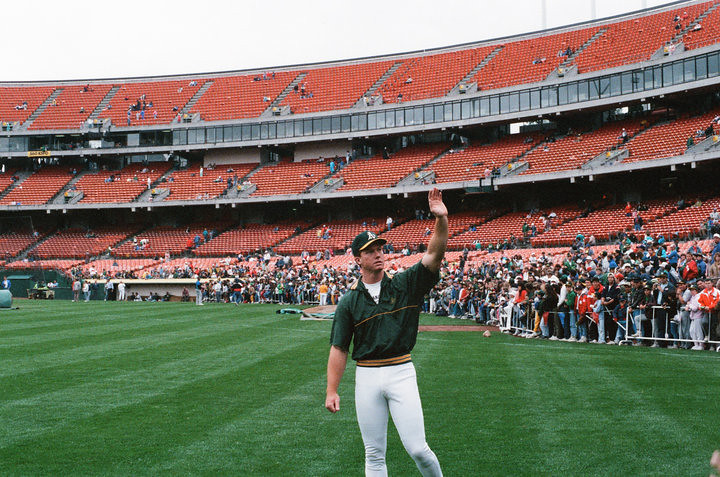

2. Mark McGwire – He originally was a draft pick of the Montreal Expos but refused to sign. After playing at USC and earning a silver medal with Team USA in the 1984 Summer Olympics, McGwire was taken 10th overall by the Athletics in the 1984 draft. He hit three home runs in an 18-game callup in 1986 and was named Rookie of the Year in the following campaign after blasting a league-high and a then-rookie record 49 home runs (third in team history), driving in 118 runs and topping the American League with a .618 slugging percentage. McGwire was an All-Star in his first six full seasons, reaching the 30-homer mark five times, posting at least 100 RBIs on three occasions, and winning a gold glove and a silver slugger. He also won the 1992 All-Star Home Run Derby in San Diego.

“Big Mac” was limited by foot and back injuries in 1993-94, but he returned to form over the next three seasons, earning All-Star selections and once again hitting prodigious home runs at a remarkable rate. He led the league with 52 home runs (second in franchise history), as well as on-base and slugging percentages (his .730 mark was also second in team history), in 1996 and was even better the following year. Despite hitting 34 home runs, McGwire was sent to the Cardinals at the trade deadline and proceeded to hit 24 more in just 51 games in St. Louis, giving him a major league-leading 58 despite not topping either circuit. In 12 seasons in Oakland, he hit a franchise record 363 home runs and ranks third in strikeouts (1,043), fourth in RBIs (941) and walks (847), seventh in total bases (2,451) and tenth in runs (773) to go with 1,157 hits, 195 doubles and a .260 average in 1,239 games. A nine-time All-Star with the A’s, McGwire also played in three straight World Series and was a part of the 1989 championship team. He totaled 12 runs, 26 hits, four homers and 13 RBIs in 32 postseason games.

By this time, baseball was in a funk after the latest labor unrest, which included a lockout that cost the league its postseason and World Series in 1994. Attendance was dropping and the sport needed a spark. Cue the home run chase of 1998. McGwire was ahead of record-holder Roger Maris‘ pace with 27 entering June, but Sammy Sosa hit 20 in the month, and his 33 overall tied him with Ken Griffey Jr. for second, four behind McGwire. Griffey fell off over the next two months, but the two others entered September tied with 55 homers, still ahead of record pace. McGwire broke the record against Sosa and the Cubs on September 8 with a 341-foot line drive over the left field wall (his shortest of the season). Sosa kept pace and the pair entered the final weekend tied with 65. The Cubs’ slugger took a brief lead, but “Big Mac” hit five in the final series against the Expos to finish with 70 to Sosa’s 66. However, Sosa got the last laugh, edging out his counterpart for the MVP Award.

McGwire won the Lou Gehrig Award and lead the league with 65 homers and 147 RBIs the following year, but his stats declined over the next two seasons, and he retired in 2001. Over the next few years, McGwire and many other players would feel the pressure to come clean about steroid use, thanks to a book by former teammate Jose Canseco, several stories in the press and an investigation by the U.S. House of Representatives. McGwire admitted to taking the muscle enhancer androstenedione in an Associated Press story and Canseco claimed he personally injected him with performance-enhancing drugs. He refused to answer questions during the House hearing but finally admitted to using steroids in 2010. McGwire was the hitting coach of the Cardinals for the next three seasons and held the same role for the Dodgers and Padres until he left in 2018. Although he hit 583 home runs and drove in 1,414 runs over 16 seasons, the PED use kept him out of the Hall of Fame, with him never even receiving 25 percent of the vote during his 10 years on the ballot.

1. Jimmie Foxx – He had a strong physique built by working on his parent’s farm, and he used that frame to launch long balls at a prodigious rate throughout his 20-year career. Originally a catcher when he signed as a 17-year-old in 1925, Foxx played first base (and occasionally at third) once the Athletics acquired Mickey Cochrane. With its collection of young talent, Philadelphia ascended to the top of the American League, winning three straight pennants and two championships from 1929-31. In those three World Series, Foxx batted .344 with 11 runs, 22 hits, four home runs and 11 runs batted in.

The jovial Foxx had a good relationship with the press, who gave him his “Beast” nickname. He earned it with his performance in 1932. He took aim at Babe Ruth‘s home run record, finishing just short with 58 (a team record) while also smacking a career-best 213 hits, leading the league with 151 runs (second in franchise history), 169 RBIs, a .749 slugging percentage and 438 total bases (all three are franchise records) and finishing second with a .364 batting average, leading to him winning the MVP Award. “Double X” followed that with a Triple Crown performance, topping the American League with a .356 average, 48 homers and 163 RBIs (as well as a .703 slugging percentage and 403 total bases) and earning Most Valuable Player honors for the second straight year. Overall, Foxx produced at least 30 home runs, 100 RBIs and 150 hits in an astounding 12 consecutive seasons, including the first seven with Philadelphia. In addition to his batting crown, he led the league in home runs and slugging percentage three times each, RBIs and total bases twice and strikeouts five times (although he never reached 100).

Foxx played in the first three All-Star Games, moving to his secondary position of third base to accommodate Lou Gehrig. Not only did he hit more home runs in the 1930s (415), but his career total of 534 ranked second behind only Ruth when he retired, and he maintained that spot on the all-time list for nearly 30 years. Despite all the accolades and success of the Athletics, the Great Depression took its toll on the team and its owner. Connie Mack sold off most of Philadelphia’s talented players, but Foxx continued his fantastic play, both on offense and defense (he won two fielding titles at first base with the A’s). However, injuries would begin to creep in, beginning with an incident during a postseason exhibition game in Canada. In days without batting helmets, Foxx was struck in the head by a pitch. Although he was diagnosed with a concussion and had a brief stay in the hospital, he would suffer from sinus problems for the rest of his life.

“Beast” began the 1935 season by returning to his original catcher spot, but he played more at the corner infield positions thanks to injuries to others. Following a last-place season, he was traded to the Red Sox and continued to be arguably the most productive player in baseball (including another MVP in 1938) over his seven seasons in Boston. However, during that time, he became plagued by serious sinus problems and severe nosebleeds, which led to him using alcohol to dull the pain. Years of playing in-season exhibitions and postseason barnstorming tours, as well as other nagging injuries, caused his production to decline sharply. Foxx was sold to the Cubs in 1942 and retired after the season. Following a year off, he returned as a player-manager in Chicago and finished his career back in Philadelphia with the Phillies in 1945, where he not only played his typical first and third base but pitched in nine games as well.

Foxx ended his 11-year stint with the Athletics (1925-35) as the all-time franchise leader in on-base (.440) and slugging percentage (.640), and he ranks second in batting average (.344), home runs (302) and RBIs (1,075), third in total bases (2,813), fourth in runs (975), sixth in triples (79) and seventh in hits (1,492) to go with 257 doubles in 1,256 games. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1951, spent the next season as the manager for the Fort Wayne Daisies in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, served as manager of the University of Miami baseball team for two years and was hitting coach for the Red Sox in 1958. However, depression, alcoholism and bad investments used up his money and led to job-hopping and medical issues later in life. Foxx and his brother were having dinner in Miami in July 1967 when he choked on his food and died at age 59.

Third Basemen

Honorable Mentions – Lafayette “Lave” Cross was born as Vratislav Kriz to parents who emigrated from the Bohemia region of Czechoslovakia to Milwaukee and later moved to Cleveland. After a two-year stint with the Louisville Colonels of the American Association, he spent most of the rest of his career in Philadelphia, including time in the AA and Players’ League as well as long runs with both major league clubs in the City of Brotherly Love. Cross became one of the best fielding third basement of the Dead Ball Era, winning five fielding titles overall. He jumped ship to the National League and joined the Athletics in 1901, helping the club win two pennants and a World Series in his five-year run (1901-05).

Cross’ best season was 1902, when he batted .342 with 90 runs, 191 hits, 108 RBIs (without hitting a home run) and a career-best 25 stolen bases. Despite being one of the best players at hitting behind and advancing runners, he was starting to be slowed by age. Cross batted just .105 (2-for-19) in the 1905 World Series as the Athletics fell to the Giants. Owner Connie Mack released his captain so he could sign with Washington, where he spent his final two seasons. Cross played and managed in the minor leagues before coaching at Ohio Wesleyan University in 1914. While walking to his job at an auto factory in 1927, he suffered a heart attack and passed away at age 61.

Jimmy Dykes was a versatile player who spent at least one season as a starter at each of the four infield spots during his 15 seasons in Philadelphia (1918-32). Six of those were at third base (1922, 25-26 and 30-32), and his career coincided with the club’s return to prominence. Dykes batted at least .300 five times, including twice at third base, and he maintained solid production despite hitting in the lower third of the batting order most of the time. He was an integral part of a team that won three straight pennants and two championships, totaling six runs, 17 hits, four doubles, one home run and 11 RBIs in 18 World Series games. With the Great Depression wreaking havoc on the nation, as well as the Athletics, Dykes was traded to the White Sox, where he was selected to play in the first two All-Star Games during his five-year run. Following his playing career, he was the manager for both teams, including replacing the legendary Connie Mack during the franchise’s final years in Philadelphia.

Michael “Pinky” Higgins got his nickname from his rosy complexion as an infant. He had a brief callup with the Athletics in 1930 and spent the next two full seasons in the minors before returning to Philadelphia when the club started selling off its best players after the Great Depression. Higgins manned the “hot corner” for the next four years, earning two All-Star selections and was voted to start in the 1934 Midsummer Classic (but Foxx started there instead). Following four seasons of at least 150 hits and 80 RBIs, he joined Foxx again after the Athletics traded him to the Red Sox. Higgins was a player-manager for a Naval baseball team during World War II and played for Boston and Detroit before retiring after the 1946 season.

Following his playing career, Higgins worked his way through the Red Sox system as a minor league manager and was named to the same position in the majors in 1955, helping Boston to a 15-game improvement. Higgins stayed with the Red Sox for eight seasons (with a stint in 1959-60 where he was fired as a manager and worked as a special assistant before being talked into returning). He became general manager late in the 1960 season, but the team failed to make the playoffs during his tenure. Higgins went 560-556 in eight seasons, despite claims of racism (which were suspect, considering he started three black players, and the accusations weren’t made until after his death). He was fired as skipper in 1962 and as general manager three years later. Higgins worked as a scout for the Astros but drinking took its toll. He was convicted of DWI in an accident that killed a Louisiana highway worker, and he suffered a heart attack two days after he was released from prison in 1969 and died at age 59.

5. Matt Chapman – A first-round pick by Oakland in 2014, he made his debut three years later. During his five seasons in the Bay Area (2017-21), Chapman was an excellent fielder as well as a solid power hitter and base runner. He won three gold gloves, two platinum gloves, two Wilson Defensive Player of the Year Awards and was named the league’s Overall Defensive Player in 2018. Chapman’s best season at the plate was 2019, when he earned his only All-Star selection to date after setting career bests with 36 home runs and 91 runs batted in. Chapman had surgeries on his thumb, shoulder and hip during his tenure with Oakland, which ended with a trade to Toronto before the 2022 season. He finished with 338 runs, 509 hits, 125 doubles, 111 home runs, 296 RBIs and 999 total bases in 573 games with the Athletics. “Pegasus” also holds the franchise record for most strikeouts in a season when he fanned 202 times in 2021. After two seasons with the Blue Jays, he signed with the Giants in 2024

4. Carney Lansford – A former Little League World Series finalist, he had solid runs with the Angels and Red Sox (including a batting title with Boston in 1981) before he was traded to the Athletics after the 1982 season to make room for future Hall of Famer Wade Boggs. Lansford’s first year in Oakland was marred by wrist and ankle injuries as well as the loss of his first child after an illness. He had a solid season the next year but missed considerable time in 1985 after fracturing his wrist when he was hit by a pitch.

The Athletics continued to improve in the standings over the second half of the 1980s, and Lansford was integral to their success. He strung together five straight quality seasons, including his only All-Star selection in 1988 and stealing 37 bases while tying his career high with a .336 average the following year. Lansford got even better in the playoffs, amassing 15 runs, 34 hits, two home runs and 15 RBIs in 29 postseason games and hitting a club-best .438 during their World Series victory over the Giants in 1989.

Lansford suffered cartilage and ligament damage to his left knee and right shoulder in a snowmobile accident, and he played just five games in 1991. He batted .262 and drove in 75 runs the following year before retiring. In 10 seasons with the Athletics (1983-92), Lansford batted .288 and totaled 617 runs, 1,317 hits (tied for tenth in franchise history), 201 doubles, 94 homers, 548 RBIs, 146 stolen bases and 1,846 total bases in 1,203 games. The three-time fielding champion and 1992 Hutch Award winner coached with four major league teams before finishing his coaching career with the Rockies 2012.

3. Eric Chavez – The 1996 first-round pick was in the majors two years later and spent the next 13 seasons with Oakland (1998-2010). In that span, Chavez had seven straight seasons with at least 20 home runs, drove in 100 or more runs four times and won six straight gold gloves. He won his only silver slugger in 2002 after batting .275 with 34 homers and 109 RBIs. Injuries caused a decline in his production and playing time over the final four years of his tenure in the Bay Area, with back and shoulder being the biggest culprits.

Chavez signed with New York in 2011 and spent two years each with the Yankees and Diamondbacks before retiring after the 2014 season. He is fifth in franchise history in strikeouts (922), sixth in home runs (230), seventh in doubles (282) and RBIs (787) and ninth in total bases (2,288) to go with a .267 average, 730 runs and 1,276 hits in 1,320 games. His tenure is the longest continuous run with the Athletics in club history. “Chavvy” appeared in 27 postseason contests, totaling 11 runs, 24 hits, seven doubles, three home runs and 12 RBIs. He also homered in Oakland’s four-game loss to Detroit in the 2006 ALCS. Following his playing career, Chavez was a broadcaster with the A’s a special assistant with the Yankees, a minor league coach with the Angels and a major league coach with the Mets.

2. Frank “Home Run” Baker – He was known for his slick fielding, timely hitting, bowlegged running style and 52-ounce bat. Baker quickly became one of the best players of the Dead Ball Era following his arrival in Philadelphia in 1908. The following year, he batted .305 with a league-leading 19 triples and, after an “off year,” he tied Davis’ major league mark by leading the league in home runs in four straight seasons from 1911-14. Baker also led the league in RBIs twice, and he had his best season in 1912 when he led the league with 10 home runs and set career highs with a .347 average, 116 runs, 200 hits, 21 triples (also a team record), 40 stolen bases and a league-leading 130 runs batted in.

While Baker’s 96 career home runs seem low in this day and age, it was more than respectable in his time, and if he had played in any later era, he would have had far more. His nickname didn’t come from the number of homers he hit, but rather, their timeliness. During the 1911 World Series against the Giants, Baker hit home runs in consecutive days, batted .375 and hit nine hits and five RBIs in the six-game victory. He was a part of four pennant winners and three championship teams, totaling 15 runs, 31 hits, seven doubles, three homers and 18 RBIs in 20 postseason games.

In 1914, following a fourth pennant in five years, owner and manager Connie Mack began selling off his top players to save money. Baker stuck around but when Mack refused to give him a higher salary, so he sat out the year, playing on independent teams in the Northeast. Baker was eventually sold to the Yankees, where he spent the rest of his career. He ranks third in franchise history in triples (88), sixth in average (.321) and ninth in stolen bases (172), and he also amassed 573 runs, 1,103 hits, 194 doubles, 48 home runs, 612 RBIs and 1,617 total bases in 899 games. He was also one of the best fielders of his era at the “hot corner,” leading the league in putouts four times and winning the fielding title in 1911.

Baker’s play in New York was solid but did not reach the levels it had in Philadelphia, and he took the 1920 season off after his wife died from scarlet fever. He returned for two more years as a part-time player before retiring to work on his family farm. In addition, he served several roles in his small Maryland hometown, including town board member, tax collector, bank director and volunteer fireman. Baker also managed in the minor leagues, where he was credited with discovering Foxx and selling him to the Athletics. He was finally elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in 1955. Baker died of a stroke in 1963 at age 77.

1. Sal Bando – A standout at Arizona State, he was selected by the Kansas City Athletics in the sixth round of the inaugural draft in 1965. He had brief call-ups in each of the next two years before taking over the starting role when the team moved to Oakland in 1968. Bando was named captain two years prior and responded with a .281 average and career highs with 31 homers and 113 RBIs. He earned four All-Star selections and finished in the top five of the MVP voting three times, including a runner-up finish in 1971, when he batted .271 with 24 home runs and 94 runs batted in.

Bando provided leadership and stability in a time when the team changed managers frequently despite success on the field. The Athletics won five consecutive division titles in the early 1970s and three straight World Series during this time, with their third baseman playing a crucial role. Bando had seven hits, and his only RBI was an insurance run in a 3-1 victory over the Reds in Game 7 in 1972, giving the club its first title in 42 years. The “Mustache Gang” overcame the interference of owner Charley Finley to beat the Mets the following year and topped the Dodgers in 1974, although Bando did little in either series. Overall, he appeared in 39 postseason games with the Athletics, totaling 20 runs, 34 hits, six doubles, five home runs and 12 RBIs.

“Captain Sal” was a vocal leader against Finley, who was actively trying to sell of his team’s best players and refused to play them after Commissioner Bowie Kuhn voided the moves. The durable star led the team with 27 home runs and stole a career-high 20 bases in what turned out to be his final year with the club. Free agency had begun in baseball, with several A’s players leaving for greener pastures. Bando signed with the Brewers and spent the final five seasons of his career in Milwaukee. In 11 seasons with Kansas City/Oakland (1966-76), he ranks fourth in franchise history in games (1,468), fifth in RBIs (796), sixth in walks (726) and ninth in home runs (192) to go with 737 runs, 1,311 hits, 212 doubles and 2,149 total bases.

Although he never won a gold glove, Bando led American League third baseman in putouts twice and was considered the best at the position other than Baltimore’s Brooks Robinson. Bando retired after the 1981 season and kept busy, starting an investment company with former Milwaukee Bucks guard Jon McGlocklin and worked in the Brewers’ front office. He was a special assistant to the general manager for 10 years before taking on the GM role in Milwaukee from 1991-99. Bando passed away after a battle with cancer in 2023 at age 78.

Upcoming Stories

Oakland Athletics Catchers and Managers

Oakland Athletics First and Third Basemen

Oakland Athletics Second Basemen and Shortstops – coming soon

Oakland Athletics Outfielders and Designated Hitters – coming soon

Oakland Athletics Pitchers – coming soon

Previous Series

A look back at the New York Yankees

New York Yankees Catchers and Managers

New York Yankees First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

New York Yankees Second Basemen and Shortstops

New York Yankees Outfielders

New York Yankees Pitchers

A look back at the New York Mets

New York Mets Catchers and Managers

New York Mets First and Third Basemen

New York Mets Second Basemen and Shortstops

New York Mets Outfielders

New York Mets Pitchers

A look back at the Minnesota Twins

Minnesota Twins Catchers and Managers

Minnesota Twins First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Minnesota Twins Second Basemen and Shortstops

Minnesota Twins Outfielders

Minnesota Twins Pitchers

A look back at the Milwaukee Brewers

Milwaukee Brewers Catchers and Managers

Milwaukee Brewers First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Milwaukee Brewers Second Basemen and Shortstops

Milwaukee Brewers Outfielders

Milwaukee Brewers Pitchers

A look back at the Miami Marlins

Miami Marlins Catchers and Managers

Miami Marlins First and Third Basemen

Miami Marlins Second Basemen and Shortstops

Miami Marlins Outfielders

Miami Marlins Pitchers

A look back at the Los Angeles Dodgers

Los Angeles Dodgers Catchers and Managers

Los Angeles Dodgers First and Third Basemen

Los Angeles Dodgers Second Basemen and Shortstops

Los Angeles Dodgers Outfielders

Los Angeles Dodgers Pitchers

A look back at the Los Angeles Angels

Los Angeles Angels Catchers and Managers

Los Angeles Angels First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Los Angeles Angels Second Basemen and Shortstops

Los Angeles Angels Outfielders

Los Angeles Angels Pitchers

A look back at the Kansas City Royals

Kansas City Royals Catchers and Managers

Kansas City Royals First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Kansas City Royals Second Basemen and Shortstops

Kansas City Royals Outfielders

Kansas City Royals Pitchers

A look back at the Houston Astros

Houston Astros Catchers and Managers

Houston Astros First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Houston Astros Second Basemen and Shortstops

Houston Astros Outfielders

Houston Astros Pitchers

A look back at the Detroit Tigers

Detroit Tigers Catchers and Managers

Detroit Tigers First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Detroit Tigers Second Basemen and Shortstops

Detroit Tigers Outfielders

Detroit Tigers Pitchers

A look back at the Colorado Rockies

Colorado Rockies Catchers and Managers

Colorado Rockies First and Third Basemen

Colorado Rockies Second Basemen and Shortstops

Colorado Rockies Outfielders

Colorado Rockies Pitchers

A look back at the Cleveland Guardians

Cleveland Guardians Catchers and Managers

Cleveland Guardians First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Cleveland Guardians Second Basemen and Shortstops

Cleveland Guardians Outfielders

Cleveland Guardians Pitchers

A look back at the Cincinnati Reds

Cincinnati Reds Catchers and Managers

Cincinnati Reds First and Third Basemen

Cincinnati Reds Second Basemen and Shortstops

Cincinnati Reds Outfielders

Cincinnati Reds Pitchers

A look back at the Chicago White Sox

Chicago White Sox Catchers and Managers

Chicago White Sox First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Chicago White Sox Second Basemen and Shortstops

Chicago White Sox Outfielders

Chicago White Sox Pitchers

A look back at the Chicago Cubs

Chicago Cubs Catchers and Managers

Chicago Cubs First and Third Basemen

Chicago Cubs Second Basemen and Shortstops

Chicago Cubs Outfielders

Chicago Cubs Pitchers

A look back at the Boston Red Sox

Boston Red Sox Catchers and Managers

Boston Red Sox First and Third Basemen

Boston Red Sox Second Basemen and Shortstops

Boston Red Sox Outfielders and Designated Hitters

Boston Red Sox Pitchers

A look back at the Baltimore Orioles

Baltimore Orioles Catchers and Managers

Baltimore Orioles First and Third Basemen

Baltimore Orioles Second Basemen and Shortstops

Baltimore Orioles Outfielders and Designated Hitters

Baltimore Orioles Pitchers

A look back at the Atlanta Braves

Atlanta Braves Catchers and Managers

Atlanta Braves First and Third Basemen

Atlanta Braves Second Basemen and Shortstops

Atlanta Braves Outfielders

Atlanta Braves Pitchers

A look back at the Arizona Diamondbacks

Arizona Diamondbacks Catchers and Managers

Arizona Diamondbacks First and Third Basemen

Arizona Diamondbacks Second Basemen and Shortstops

Arizona Diamondbacks Outfielders

Arizona Diamondbacks Pitchers