This is the first article in a series that looks at the five best players at each position for the Oakland Athletics. In this installment are catchers and managers.

The Athletics’ 124-year history has been defined by several runs of success followed by long stretches of poor play usually brought about by selling off top players from winning squads. The man responsible for the early years of the franchise was Connie Mack, who was born as Cornelus McGillicuddy in 1862. He was a player-manager with the Pirates and later the Western League’s Milwaukee Brewers. When the Western League turned into the American League in 1901, president Ban Johnson asked Mack to run the new franchise in Philadelphia that would compete with the Phillies for players and fans.

The team was called the Athletics, a named that had been used by at least half a dozen professional teams in the city dating back to the National Association entry in 1871. There was also a team by that name in the National League’s first season in 1876, although it was removed after refusing to play its final set of games against teams in the western portion of the circuit. The most successful incarnation of the Athletics played in the American Association from 1882-90 and won a league pennant in its second season.

The American League’s Athletics, like many of the Junior Circuit’s other early teams, was initially bankrolled by Cleveland owner Charles Somers. Mack found a local owner in Ben Shibe, the owner of the A.J. Reach Company, which made baseball equipment and was a minority owner of the Phillies. In exchange for his 50 percent share, Shibe was promised that his company would provide the baseball for the new league. Mack retained a 25 percent part of the ownership, with the rest split between Philadelphia sports writers Frank Hough and Sam Jones, who sold their shares to Mack in 1912, making him and Shibe equal partners.

Mack raided the crosstown Phillies for players, especially future Hall of Fame second baseman Napoleon Lajoie. However, the National League club fought this player poaching and the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled in their favor. To get around this, President Johnson moved Lajoie and others to Cleveland and they sat whenever the Naps played in Philadelphia. Meanwhile, Mack restocked his roster after the debacle and the Athletics became one of the best teams in the young league. Thanks to stellar pitching, Philadelphia won six pennants in its first 14 years of existence and won three World Series championships in a four-year stretch from 1910-13. The Athletics won their first pennant in 1902, but the in-state rival Pirates refused to play against them for the title. John McGraw, a former American League manager who jumped to the N.L.’s Giants labeled the A.L. champions a “White Elephant,” a derisive term of the time that was used on things that were costly and impractical. Mack responded by adopting the animal as a mascot of sorts, and the team wore a white elephant patch on its uniforms for nearly three decades afterward.

The downfall of the early Athletics’ dynasty was the Federal League, a circuit which, like other entities from the late 1800s, promised players more money. Mack refused to match the salaries his top players were offered and lost many of his stars. Philadelphia went from 99 wins in 1914 to 43 the following year and 36 in 1915. The team spent seven straight years in the American League cellar, losing 100 or more games in six of those seasons. Although Mack was getting past the age of most managers at the time, he brought in young players who blossomed into stars and led to another run of success. The Athletics finished above .500 for nine straight years from 1925-33 and battled the Yankees for supremacy in the American League. They won three straight pennants from 1929-31 and won titles in the first two years of that run.

However, Shibe passed away in 1922 from complications due to a car accident, leaving his share of the team to his sons, Thomas and John. When they both passed away in the late 1930s, Mack bought out some of the shares from their estate and became majority owner. However, his sole form of income was the Athletics, and Mack, like many others, was hit hard by the Great Depression. Once again, Mack sold off his best players, leading to another long run of futility. Over the next two decades, Philadelphia had just three winning seasons, finished in last place 11 times, losing 100 or more games in seven of those campaigns. Mack continued to run and manage the team long after many said he was capable of doing so. The 1950 season was his 50th with the team and, at 87 years old, he was showing signs of his age. Mack napped during games, had memory lapses and made bad coaching decisions that his assistants had to fix. Despite vowing never to step down, Mack’s sons, Earle and Roy, got him to step down as manager, although he stayed on as team president.

The end of the Athletics in Philadelphia is convoluted and difficult to explain. Mack’s first wife Margaret (mother of Earle and Roy) died in 1892. He married his second wife, Katherine, in 1910 and they had four girls and a boy (Connie Jr.). Mack gave his three sons equal shares in the club, and he also gave some to Katherine, in addition to the ones still retained by the heirs of the Shibe family. Connie Jr., his mother and the Shibe contingent knew the team would not be successful in its current state, so they wanted to sell the club. Earle and Roy refused and eventually bought out the others, leaving them and their father in control of the team with the purchased shares going into the club treasury. However, to do that, the brothers took out a loan, using Shibe Park as collateral.

Although the Athletics had three straight winning seasons in the early 1950s, the club was suffering at the gate and the Macks were barely breaking even on the mortgage. Eventually, Earle no longer wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps as manager and executive, leaving Roy in control of the team’s day-to-day operations. Two groups stepped up to buy the Athletics, a syndicate of nine business owners that tentatively agreed to keep the team in Philadelphia, and Arnold Johnson, a Chicago business owner who also owned Yankee Stadium as well as the home of New York’s top farm team in Kansas City. Roy agreed and reneged on deals with both sides before he, Earle and their father agreed to sell to the Yankee-backed Johnson and let the team move to Kansas City. Mack was in attendance at the team’s first game in their new home, but he did not live very much longer, passing away due to complications from hip surgery in 1956 at age 93.

Johnson sold his ownership to both stadiums and took over the operation of the Athletics, but the results left a lot to be desired. In 13 seasons playing in the “Heart of America,” the team never had a winning record or even finished in the top half of the American League. During that time, the Athletics were best known as being a feeder team to the Yankees, sending nearly a dozen players to become talented additions to an already stellar squad in New York. Johnson suffered a heart attack and died in 1960 and his wife sold his 52 percent share of the team to Charlie Finley, a self-made millionaire in the insurance industry. He soon bought out all the other shares of the Athletics and immediately tried to move the club.

Finley was brash and rude, with his attitude and ego angering nearly everyone associated with his team, including fans, players, front office staff, fellow owners, media members and even the commissioner. What started as a sideshow (complete with a live mule mascot) in Kansas City turned serious once Finley was finally allowed to move the team to Oakland in a deal that also led to a pair of expansion teams two years later. The Athletics were a team of young stars that won five straight division titles and three championships in the early 1970s, but the group of fun-loving players known as the “Mustache Gang” were constantly being upstaged by their owner, who needed to be at the center of everything. Once star pitcher Catfish Hunter was granted free agency on a technicality after the 1974 season, and baseball’s reserve clause was ended a year later, players left Oakland in droves after their contracts expired. Finley traded or sold off the remaining stars and was forced to sell the team after his divorce in 1980.

The new man in charge of the Athletics was Walter Haas Jr., who ran the Levi Strauss clothing company. Haas bought the team to prevent a sale to Marvin Davis, a petroleum company owner who wanted to move the club to Denver. During Haas’ tenure, the Athletics won five division titles and went to three straight World Series, winning the 1989 Fall Classic that was notable because of an earthquake that shook California before the start of Game 3. Following Haas’ death from prostate cancer in 1995, the club was sold to real estate developers Stephen Schott and Ken Hofmann. During their time in charge, the “Moneyball” Athletics went over the 100-win mark twice and made four straight playoff appearances but bowed out in the Division Series each time.

Schott and Hofmann sold the team in 2005 to a group led by Lewis Wolff, another real estate developer who, in addition to owning 18 hotel and resort properties around the world, was a co-owner of the NHL’s Blues, NBA’s Warriors and the MLS team the San Jose Earthquakes. Under his watch, the Athletics won three division titles and made four playoff appearances. However, the furthest they went in the postseason was a sweep at the hands of the Tigers in the 2006 ALCS. Wolff sold his majority shares of the A’s and Earthquakes to John Fisher, the son of Donald and Doris Fisher, who founded the Gap clothing retailer. Fisher and his father were part owners of the Giants in the 1990s and helped the team stay in San Francisco and avoid moving to Tampa Bay.

Fisher and the city of Oakland have had a very public feud for the past several years, with the owner trying to move the team out of what he says is a crime-ridden and economically depressed area and the city claiming the owner is just trying to milk its citizens out of more tax dollars for a new stadium when he refuses to spend his money on fielding a quality team. No matter who is more to blame in this situation, the result is that Oakland will host its last Major League Baseball game in 2024. The Athletics will play at the home of the Giants’ Triple-A affiliate in Sacramento for three seasons before joining the Raiders in a move to Las Vegas. The city of Oakland will have lost three teams in less than a decade, with the Warriors moving across the Bay to San Francisco in 2019 and the Raiders leaving town the following year.

The Athletics were competitive in the early part of Fisher’s tenure, earning three straight playoff berths from 2018-2020, but lost more than 100 games in each of the past two seasons. The reason for the failure is the owner’s willingness to trade away top talent to keep the payroll low, much like Mack, Johnson and Finley did previously. Now, the few fans who are bothering to show up to the Oakland Coliseum this season will watch a team of basically unknowns try and compete with the up-and-coming Mariners, the 2023 champion Rangers and the Astros, who have been to the playoffs in the past seven years, played in the World Series four times and won two titles, including in 2022.

The Best Catchers and Managers in Oakland Athletics History

Catchers

Honorable Mentions – Ossee Schrecongost was a journeyman before coming to Philadelphia during the 1902 season. Although he batted .324 that year, he was considered a below-average hitter overall. However, “Schreck” was stellar behind the plate, winning two fielding titles and topping the American League in putouts six times. He was a part of two pennant-winning clubs and won a title with Philadelphia in 1905 along with Rube Waddell, his best friend and future Hall of Fame pitcher. After Schrecongost retired after the 1908 season, he was a scout for the Athletics. Both batterymates passed away in 1914, Waddell in April and “Schreck” in July at age 39.

Warren “Buddy” Rosar was a star with the Yankees and Indians before joining the Athletics in 1945. Over the next five seasons (1945-49), he was a three-time All-Star, won three fielding titles and led the league twice in assists and runners caught stealing for a team who was going through unrest in the front office. Rosar was an excellent fielder and great at handling pitchers, but he had several injuries as he aged, including torn cartilage and an eye infection. He spent his final two years with the Red Sox and ended his 13-year career in 1951. Rosar worked at a war material factory during World War II and held a variety of positions in his native Buffalo, including as an engineer at a Ford plant. He passed away in 1994 at age 79.

Dave Duncan was a solid power hitter and fielder during his seven-year tenure with the Athletics (1964 and 67-72), but his .217 batting average left much to be desired. He was an All-Star in 1971 and a starter on the team that won the World Series the following year, but like many other Oakland players, he fought over salary with penny-pinching owner Charlie Finley and was traded to Cleveland. After he retired following the 1976 season, Duncan focused on working with pitchers. He started with the Indians and Mariners before joining former teammate Tony LaRussa as a pitching coach with the White Sox. The pair was fired during the 1986 and both latched on with the Athletics, where they helped the club reach the World Series in three straight seasons. When LaRussa left to manage in St. Louis, Duncan joined him and spent the next 15 years with the Cardinals. He left in 2012 when LaRussa retired and his wife, Jeanine, had been diagnosed with a brain tumor. She passed away a year later and Duncan has spent the past decade as a consultant with the Diamondbacks and White Sox.

Kurt Suzuki was a second-round pick of the Athletics in 2004 and played in the MLB Futures Game two years later. He made his debut with Oakland in 2007 and put together four straight solid offensive seasons. Suzuki drove in a career-high 88 runs in 2009 and over seven seasons with the A’s in two stints (2007-12 and ’13), he had 653 hits, 136 doubles, 59 home runs and 309 RBIs in 718 games. He played with four other teams and retired in 2022 after a 16-year career. Suzuki earned his only All-Star selection as a member of the Twins in 2014 and was a backup catcher on the Nationals when they won the World Series in 2019.

Stephen Vogt wasn’t really given a chance in Tampa Bay, but he made the most of his opportunity in Oakland, earning two All-Star selections, including 2015, when he had his best year with a .261 average and career-high marks with 18 home runs and 71 runs batted in. Despite having a strong presence, both in the community and the clubhouse, Vogt was released midway through the season and signed with the Brewers. He missed most of the next season after having surgery to repair a damaged rotator cuff, labrum and capsule in his right arm. Vogt played with the Giants, Diamondbacks and Braves before returning to the Athletics for one final season in 2022. In six seasons with Oakland (2013-17 and ’22), he had 409 hits, 56 homers and 221 RBIs in 528 games. Vogt was the bullpen coach for the Mariners for one season before being named manager of the Guardians in 2024.

5. Ralph “Cy” Perkins spent 15 of his 17 major league seasons in Philadelphia (1915 and 17-30). He had a solid six-year run as a full-time starter and above average run producer with the position as the Athletics worked their way out of the American League cellar. Perkins was a durable backstop and arguably the best in the A.L. at the time, especially on the defensive end. He eventually lost his job to the top player on this list, but he helped tutor the future Hall of Famer in his work behind the plate. Perkins was the backup on two straight pennant-winning clubs but did not make an appearance in either World Series.

The Athletics released Perkins before the 1931 season and he latched on with the Yankees, where he spent one year as a backup catcher and two as a coach. Perkins finished his time in Philadelphia with a .259 average, 921 hits, 174 doubles and 402 RBIs in 1,154 games. He joined the Tigers in 1934, getting one at-bat for the pennant-winning club before retiring for good and turning to coaching. He had a 15-game stint as a manager in Detroit during the 1937 but was let go the following year. Perkins spent the next 20 seasons as a scout, minor league manager and major league coach in several organizations, especially with the “Whiz Kid” Phillies of the early 1950s. He had alcohol issues for a while after losing his savings in the stock market crash and his wife, who died after an illness in 1935. Perkins beat the addiction while serving in the Navy during World War II. He coached at Valley Forge Military Academy for three years and was a public speaker. However, he once again struggled with alcohol and passed away in 1963 at age 67.

4. Gene Tenace – He spent the first eight seasons (1969-76) of a 15-year career with Oakland, helping the Athletics win three straight titles as a member of the “Mustache Gang.” The 1975 All-Star split his time mainly between catcher and first base and had 20 or more home runs in four straight seasons. Going by his middle name instead of his first name, Fury, Tenace amassed 603 hits, 121 home runs and 389 RBIs in 805 games with Oakland.

Tenace had his moments during the playoffs. He was named MVP of the 1972 World Series upset over the “Big Red Machine,” finishing with four home runs and nine RBIs and becoming the first player to hit a home run in his first two at-bats in the Fall Classic. After showing consistent power even after his move to first base, Tenace left Oakland and signed with San Diego after free agency began following the 1976 season. He won a title as a backup with the Cardinals in 1982 and retired after the following season, which he spent with the Pirates.

Nicknamed “Steamboat” because of his build, Tenace became a coach and instructor for more than 20 years following his playing career. He was an interim manager in Toronto when Cito Gaston missed time with a herniated disk, posting a 19-14 record. Tenace was the bench coach for a Blue Jays team that won back-to-back titles the following two seasons, giving him six total championships in his baseball tenure. He finished his career with a second stint as Toronto’s hitting coach in 2008-09.

3. Frankie Hayes – He took over for one of the legends of the game in the first half of the 20th century and had a four-year run as one of the best-hitting catchers in the game and also one of the most durable (he played in a then-record 312 straight games). Hayes earned four All-Star selections in 11 seasons with Philadelphia (1933-34, 36-42 and 44-45), and he led A. L. catchers in putouts and double plays twice each. Hayes was traded to the Browns but sent back to the Athletics after a little more than a year. Following a trade to the Indians, he caught Bob Feller‘s no-hitter against the Yankees in April 1946 and provided the game’s only run with a ninth-inning homer.

Hayes finished his career in Philadelphia with a .270 average, 450 runs, 906 hits, 167 doubles, 101 home runs, 503 RBIs and 1,428 total bases in 992 games. He had the misfortune of playing for the Athletics during some of their worst years and never played in the World Series. “Blimp” also spent time with the White Sox and Red Sox before his 14-year career came to an end in 1947. Following his playing days, he ran a sporting goods store in New Jersey. Hayes died in 1955 at age 40 due to a retroperitoneal hemorrhage (bleeding in the rear abdominal cavity).

2. Terry Steinbach – He converted from third base to catcher after a stellar career at the University of Minnesota, where he played alongside his two older brothers. Steinbach was drafted by Oakland in the ninth round of the 1983 draft and joined the team three years later, hitting a home run against Cleveland in his first at-bat late in the 1986 season. He became the starter the following season and put up strong offensive numbers, but he was sidelined for more than a month after suffering an eye injury when he was hit by a throw during infield practice.

Steinbach earned his first of three All-Star selections in 1988, winning the game’s MVP Award after hitting a third-inning home run (and becoming the first player in baseball history to hit home runs in both his first regular season and All-Star Game at-bats). The A’s were becoming a powerhouse in the American League, and he was a solid contact hitter for a team that made three straight World Series appearances. Steinbach drove in seven runs during the 1989 championship victory and hit a home run in Game 2 against the Giants. His best season was his last in Oakland in 1996, when he batted .272, bashed 35 home runs and drove in 100, both career-best totals by a wide margin.

After the season, Steinbach signed with his hometown Twins, where he spent his final three years and caught his second no-hitter (Dave Stewart with Oakland in 1990 and Eric Milton with Minnesota in 1999). After his retirement, the 1994 fielding champion coached a local high school team, worked as Twins’ minor league instructor and runs an endowment program that gives scholarships to students from the high school system he attended in New Ulm, Minnesota. Steinbach finished his 11-year run in Oakland (1986-96) with 498 runs, 1,144 hits, 205 doubles, 132 home runs, 595 RBIs, a .275 average and 1,773 total bases in 1,199 games.

1. Gordon “Mickey” Cochrane – He was one of the first truly great catchers in baseball history, excelling in every facet of the game: Hitting for average and power, baserunning and stealing, defense, throwing arm, game calling, handling pitchers, durability, competitiveness and a likeable personality. Cochrane spent the first nine seasons (1925-33) of a 13-year career with Philadelphia, helping his team make three straight World Series appearances and winning two titles. While his parents were both of Scottish descent, Cochrane got his nickname in the minor leagues when other thought he was Irish. No one outside of baseball called him “Mickey,” and he was known as Mike to friends and family.

In addition to his well-rounded abilities, Cochrane was solid statistically, finishing in the top 10 of the MVP vote five times and winning the award in 1928. He batted .300 or better and drove in at least 80 runs five times each with the Athletics, amassed more than 150 hits four times and produced a .400 or higher on-base percentage in six seasons, leading the league with a .459 mark in 1933. Despite all his accolades and qualities, Cochrane fell victim to the effects of the Great Depression. Like many others, Philadelphia owner Connie Mack was hit hard during the crisis and sold off most of his star players, with Cochrane being sent to Detroit.

Although he didn’t like the increased pressure of his new spotlight, Cochrane was named MVP for the second time in his first season in the Motor City. He became a player-manager, leading the Tigers to the World Series in his first two years with the club while being selected to the All-Star Game twice. Following the death of club owner Frank Navin in late 1935, Cochrane was made general manager in addition to his playing and managing roles. Soon, the pressure became too much. After hitting an inside-the-park grand slam against his former team in early June 1936, he got dizzy and collapsed in the dugout. Over the next few months, Cochrane alternated between managing the club and spending time in the hospital, with his high-strung, competitive nature contributing to a nervous breakdown and giving him the nickname “Black Mike.”

Cochrane’s playing career ended the following season after he was hit in the head by a pitch from Yankee starter Bump Hadley. The catcher spent a week in the hospital and nearly died from his injuries before he listened to doctors and retired. Cochrane returned to manage Detroit but was dismissed in August after being deemed too temperamental. He managed at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center outside Chicago during World War II, was the Athletics general manager in 1950 and was a scout with the Yankees later in the decade. Cochrane ranks fifth in franchise history in on-base percentage (.412), tied for sixth in average (.321), eighth in runs (823) and tied for tenth in hits (1,317) along with 250 doubles, 59 triples, 108 home runs, 680 RBIs and 2,009 total bases in 1,167 games. He added 12 runs and 14 hits in 18 World Series games with the Athletics.

A five-time pennant-winner and three-time champion, Cochrane led all American League catchers in putouts six times, won two fielding titles and led the league in assists and double plays twice each. He was the first catcher voted into the Hall of Fame by the baseball writers in 1947 (the three that preceded him were selected by the Veteran’s Committee), and his .320 career average is the best at the position among major leaguers. Cochrane spent most of his post-baseball days on his Montana ranch until he developed lymphatic cancer, which claimed his life in 1962 at age 59.

Managers

Honorable Mentions – Alvin Dark was a three-time All-Star shortstop and the 1948 Rookie of the Year during a 14-year playing career spent mainly with the Giants in the 1950s. He won a pennant as a manager in 1962 after the team moved to San Francisco and led the Indians in between stints with the Athletics, one in Kansas City and one in Oakland. In four seasons (1966-67 and 74-75), Dark had a 314-291 record and won a title in 1974 after replacing a fired future Hall of Famer who appears later on this list. Despite leading the Athletics to 98 wins in 1975, Dark was let go after Oakland was swept by Boston in the ALCS. He coached with the Cubs, had a brief managerial stint with the Padres in 1977 and was a minor league talent director and evaluator for the Cubs and White Sox in the following decade. Dark passed away in 2014 at age 92.

Ken Macha had a six-year major league career as a reserve infielder, then played four seasons in Japan before retiring in 1985. He was a minor league manager and major league coach for more than 15 years before he was hired in 2003 to replace the next man on this list. Macha had winning records in all four of his seasons on the Oakland bench (2003-06), compiling a 368-280 record in that span. He led the team to a pair of playoff appearances, including a sweep of the Twins in the Division Series, giving the Athletics their first postseason series victory since 1990. However, Macha was fired after a sweep at the hands of the Tigers in the ALCS. After two seasons leading the Brewers in 2009-10, he has not held a major league coaching position.

5. Art Howe – His 11-year playing career included a seven-year stint in Houston in which he started at three infield spots. After a four-year stint as a coach with the Rangers he managed the Astros for five seasons. Howe was a manager in the Dominican Republic, a scout for the Dodgers and a bench coach for the Rockies before taking over for a manager later on this list who was one of the most respected and popular in Athletics’ history. Oakland suffered through three losing seasons before making the playoffs in three straight seasons from 2000-02, winning at least 100 games in the final two campaigns. Although he doubted the methods of the “Moneyball” A’s under general manager Billy Beane, the team had regular season success before falling each time in the Division Series. Howe finished with a 600-533 record with the Athletics before signing with the Mets for two disappointing seasons. He spent time as a coach with the Phillies and Rangers before he retired in 2008.

4. Bob Melvin – He was a backup catcher, primarily with the Giants and Orioles, during a 10-year playing career. Melvin spent four seasons with the Brewers in a variety of roles, finishing as a bench coach in 1999. He followed that with a year in the same role with the Tigers and two with the Diamondbacks, including their title-winning season in 2001. Melvin’s managerial career started with 93-win season with Seattle in 2003, but the Mariners missed the playoffs by two games. He had a five-year run at the helm in Arizona, leading the team to the NLCS (and winning the Manager of the Year Award) in 2007 before being swept by Colorado.

Melvin took the 2010 season off before joining the Athletics on an interim basis following the firing of Bob Geren in June 2011. Over the next 11 seasons (2011-21), Oakland had a winning record seven times, earned six playoff berths, amassed 90 or more games four times and won three division titles. Despite an 853-764 record and two Manager of the Year Awards, much of the time competing with one of the league’s lowest team payrolls, Melvin could not lead the A’s past the Division Series. He left his hometown team for one further south, spending the next two years managing the Padres. Melvin missed games due to prostate surgery and COVID-19 in 2022 but led San Diego to the NLCS, which ended with a loss to Philadelphia. Following the 2023 season, he returned to the Bay Area to manage the Giants. With a 1,517-1,425 record in his first 20 seasons, Melvin enters 2024 with the second-most wins among active managers, trailing only Bruce Bochy (2,093).

3. Dick Williams – He had a 13-year playing career as a third baseman an outfielder, with his best years split between the Orioles and the Athletics when they were in Kansas City. Williams had a knack for turning around downtrodden franchises during his 21-year managerial career. He took a Red Sox team to the World Series in 1967 for the first time in two decades; he led the Expos for the only playoff appearance in their 36 years in Montreal in the strike-shortened 1981 season; the following year, he took over the Padres, led them to four straight seasons of .500 or better, including their first playoff berth and World Series appearance in 1984, as well as stints with the Angels and Mariners.

Williams’ greatest stint was his three-year run with the Athletics in the early 1970s. He led the franchise to its first postseason appearance in 40 years in 1971 and, although the A’s got swept by the powerful Orioles in the ALCS, a stellar team was in place. Oakland won the next three championships, including one against Cincinnati’s “Big Red Machine,” and the other against the upstart Mets. Williams, along with many others, took issue with owner Charlie Finley. The final straw for the manager took place during Game 2 of the World Series in 1973. With the score tied in the 12th inning, Oakland second baseman Mike Andrews made two errors and New York won the contest. Upset by the play, Finley forced Andrews to sign paperwork stating he was injured, and the owner tried to replace him on the roster. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn refused to accept that solution and forced Finley to keep Andrews on the roster.

Williams was so frustrated by the incident that he left the team even after the A’s won the World Series. He tried to sign with the Yankees but, because he had one year left on his contract, Finley demanded player compensation, which New York refused. Williams finished his three-year tenure (1971-73) with a 288-190 record and ended his career with a 1,571-1,451 mark. Following his 1988 firing from the Mariners, he worked as a scout for the Yankees until 2002. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veteran’s Committee in 2008 and passed away in 2011 at age 82 due to a ruptured aortic aneurysm.

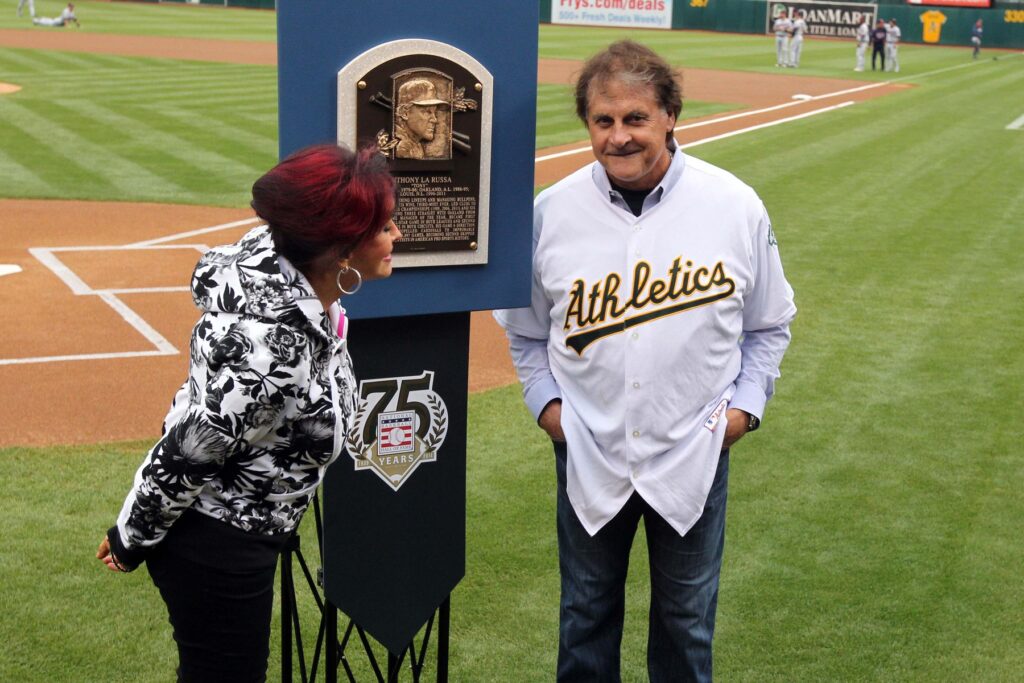

2. Tony La Russa – He appeared in 132 games over a six-year playing career, five of which were spent with the Athletics, including on in Kansas City. Following his time as a light-hitting backup infielder, La Russa earned a law degree and was admitted to the bar in Florida. However, he was still interested in baseball, spending two seasons coaching with the White Sox before being named manager during the 1979 season. He took Chicago from 90 losses in his first year to 99 wins and a division title in 1983. That season, the White Sox fell to the Orioles in the ALCS and La Russa won the AL Manager of the Year Award. However, less than three years later, both he and former minor league teammate-turned pitching coach Dave Duncan were fired by Chicago. They were hired by Oakland just two weeks later and brought the franchise back to prominence.

Led by their new manager, the Athletics won three straight pennants from 1988-90, with La Russa being named Manager of the Year in the first of those seasons. Oakland overcame a loss to Los Angels to win an earthquake-interrupted World Series against cross-bay rival San Francisco in 1989. La Russa won a fourth division title and a third Manager of the Year Award in 1992, but three losing seasons followed, and he left after amassing a 798-673 record in 10 seasons (1986-95) including four seasons with 90 or more wins and twice topping 100.

La Russa spent the next 16 years with the Cardinals, winning a fourth Manager of the Year Award and leading them to eight playoff appearances, seven division titles and two championships, including his final season in 2011, when St. Louis came back from a double-digit deficit in August to win the wild card playoff spot on the last day of the season. He was in the dugout for two memorable World Series moments, Kirk Gibson’s walk off home run for the Dodgers in Game 1 in 1988 and David Freese‘s 11th inning blast in St. Louis’ dramatic win in Game 6 in 2011. Although he was a fiery competitor and loyal to his players, La Russa’s greatest attribute to the game was his innovation. He tried batting pitchers in the eighth spot in the order, used specialty relievers in certain situations and began utilizing closers exclusively in the ninth inning. La Russa was also on the committee that expanded the replay system in 2014.

He was not always the easiest to get along with as a manager. La Russa was intense and at times had a volatile temper, especially when dealing with the press. He also was arrested on suspicion of driving under the influence in 2007. After holding executive roles with the Diamondbacks and Red Sox, La Russa returned to manager Chicago for a two-year stint with the White Sox, bringing his career full circle from his first stop. He led the club to 93 wins and a playoff berth in 2021 but retired the following season after undergoing tests on his heart. La Russa was voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2014 and left the game with a 2,884-2,499 regular season record, with his victory total ranking second behind the final name on this list.

1. Connie Mack – The son of a Civil War soldier was a catcher during an 11-year playing career who prided himself on fair play while also utilizing some of the common practices used by backstops during the late 1800s such as striking up a conversation with batters to distract them and tipping their bats as the swung at incoming pitches. Mack became manager and part-owner of the Philadelphia Athletics in the brand-new American League and sustained a record for longevity that will never be broken. Known for wearing a suit, tie and straw hat in the dugout, he managed the team for 50 years, leading the team to a winning record in half of those seasons.

Mack had two incredibly successful runs with the Athletics, leading the team to six pennants and three titles in the first 14 years of the Junior Circuit, and 1929-31, which included three straight A.L. championships and two more World Series titles. Ironically, the only year of the three that they didn’t win (1931), the “Mackmen” as they were nicknamed, set a franchise record with 107 victories, one of five times they reached the century mark in his tenure. Unfortunately for Philadelphia fans, when things were bad, they were really bad. Mack’s partner Ben Shibe, as well as his two sons, passed away by the 1930s, leaving Mack in charge with nothing but the ballclub for revenue. The eras following the team’s championship runs (especially after the Great Depression in the early 1930s) caused the owner to sell off his best players just to keep the club afloat. In all, the Athletics finished in last place in the American League 17 times and lost 100 or more games in 10 seasons.

The team had a brief renaissance in the late 1940s, but by then, the man known as the “Tall Tactician” (due to his 6-foot-2 height) was well past his prime. Mack’s advanced age (87) was leading to mental lapses on the field and his sons removed him from his post. Eventually, the team moved from Philadelphia to Kansas City and then Oakland (and now potentially Las Vegas), with the team little resembling the one Mack controlled, except for the fact that ownership still lets its best players go after periods of success and is perpetually looking for greener pastures.

Mack continued to run the team until the move to Kansas City five years after his managerial career ended. The stadium shared by both the Athletics and Phillies was renamed from Shibe Park to Connie Mack Stadium in 1953 and kept until Veterans Stadium opened in 1970. Mack was in attendance at the team’s first game in Kansas City in 1955, but his attendance declined after suffering a hip fracture after a fall in October. He passed away the following February at age 93. Mack was voted into the second class of inductees for the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Centennial Commission in 1937. His 3,731-3,948 record is far and away the best in both categories in baseball history.

Upcoming Stories

Oakland Athletics Catchers and Managers

Oakland Athletics First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters – coming soon

Oakland Athletics Second Basemen and Shortstops – coming soon

Oakland Athletics Outfielders – coming soon

Oakland Athletics Pitchers – coming soon

Previous Series

A look back at the New York Yankees

New York Yankees Catchers and Managers

New York Yankees First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

New York Yankees Second Basemen and Shortstops

New York Yankees Outfielders

New York Yankees Pitchers

A look back at the New York Mets

New York Mets Catchers and Managers

New York Mets First and Third Basemen

New York Mets Second Basemen and Shortstops

New York Mets Outfielders

New York Mets Pitchers

A look back at the Minnesota Twins

Minnesota Twins Catchers and Managers

Minnesota Twins First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Minnesota Twins Second Basemen and Shortstops

Minnesota Twins Outfielders

Minnesota Twins Pitchers

A look back at the Milwaukee Brewers

Milwaukee Brewers Catchers and Managers

Milwaukee Brewers First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Milwaukee Brewers Second Basemen and Shortstops

Milwaukee Brewers Outfielders

Milwaukee Brewers Pitchers

A look back at the Miami Marlins

Miami Marlins Catchers and Managers

Miami Marlins First and Third Basemen

Miami Marlins Second Basemen and Shortstops

Miami Marlins Outfielders

Miami Marlins Pitchers

A look back at the Los Angeles Dodgers

Los Angeles Dodgers Catchers and Managers

Los Angeles Dodgers First and Third Basemen

Los Angeles Dodgers Second Basemen and Shortstops

Los Angeles Dodgers Outfielders

Los Angeles Dodgers Pitchers

A look back at the Los Angeles Angels

Los Angeles Angels Catchers and Managers

Los Angeles Angels First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Los Angeles Angels Second Basemen and Shortstops

Los Angeles Angels Outfielders

Los Angeles Angels Pitchers

A look back at the Kansas City Royals

Kansas City Royals Catchers and Managers

Kansas City Royals First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Kansas City Royals Second Basemen and Shortstops

Kansas City Royals Outfielders

Kansas City Royals Pitchers

A look back at the Houston Astros

Houston Astros Catchers and Managers

Houston Astros First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Houston Astros Second Basemen and Shortstops

Houston Astros Outfielders

Houston Astros Pitchers

A look back at the Detroit Tigers

Detroit Tigers Catchers and Managers

Detroit Tigers First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Detroit Tigers Second Basemen and Shortstops

Detroit Tigers Outfielders

Detroit Tigers Pitchers

A look back at the Colorado Rockies

Colorado Rockies Catchers and Managers

Colorado Rockies First and Third Basemen

Colorado Rockies Second Basemen and Shortstops

Colorado Rockies Outfielders

Colorado Rockies Pitchers

A look back at the Cleveland Guardians

Cleveland Guardians Catchers and Managers

Cleveland Guardians First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Cleveland Guardians Second Basemen and Shortstops

Cleveland Guardians Outfielders

Cleveland Guardians Pitchers

A look back at the Cincinnati Reds

Cincinnati Reds Catchers and Managers

Cincinnati Reds First and Third Basemen

Cincinnati Reds Second Basemen and Shortstops

Cincinnati Reds Outfielders

Cincinnati Reds Pitchers

A look back at the Chicago White Sox

Chicago White Sox Catchers and Managers

Chicago White Sox First and Third Basemen and Designated Hitters

Chicago White Sox Second Basemen and Shortstops

Chicago White Sox Outfielders

Chicago White Sox Pitchers

A look back at the Chicago Cubs

Chicago Cubs Catchers and Managers

Chicago Cubs First and Third Basemen

Chicago Cubs Second Basemen and Shortstops

Chicago Cubs Outfielders

Chicago Cubs Pitchers

A look back at the Boston Red Sox

Boston Red Sox Catchers and Managers

Boston Red Sox First and Third Basemen

Boston Red Sox Second Basemen and Shortstops

Boston Red Sox Outfielders and Designated Hitters

Boston Red Sox Pitchers

A look back at the Baltimore Orioles

Baltimore Orioles Catchers and Managers

Baltimore Orioles First and Third Basemen

Baltimore Orioles Second Basemen and Shortstops

Baltimore Orioles Outfielders and Designated Hitters

Baltimore Orioles Pitchers

A look back at the Atlanta Braves

Atlanta Braves Catchers and Managers

Atlanta Braves First and Third Basemen

Atlanta Braves Second Basemen and Shortstops

Atlanta Braves Outfielders

Atlanta Braves Pitchers

A look back at the Arizona Diamondbacks

Arizona Diamondbacks Catchers and Managers

Arizona Diamondbacks First and Third Basemen

Arizona Diamondbacks Second Basemen and Shortstops

Arizona Diamondbacks Outfielders

Arizona Diamondbacks Pitchers

Main Image: Lance Iversen-USA TODAY Sports