Major League Baseball (MLB) has long been considered “America’s Pastime”, but it still struggles to represent the vast diversity of the United States, a problem dating back to the league’s origin at the turn of the 20th century. Despite attempts to increase participation among Black youth, MLB remains largely devoid of Black players with only 6.2% of MLB players falling under that demographic this season, and even less representation amongst managers and owners.

Yet, MLB has done the admirable, if woefully long overdue, task of bringing the Negro League history back into the mainstream by fully integrating the statistics of the Black-only league into its expansive records back in May. The league honored this often overlooked aspect of American baseball history in a special game on June 20 between the San Francisco Giants and St. Louis Cardinals at Rickwood Field. The Birmingham, Alabama stadium, the oldest in the US, served as recently deceased Giants’ legend Willie Mays’ home field during the Hall-of-Famer’s first couple seasons playing professionally as a teenager with the Negro League’s Birmingham Black Barons.

MLB History: Negro Leagues

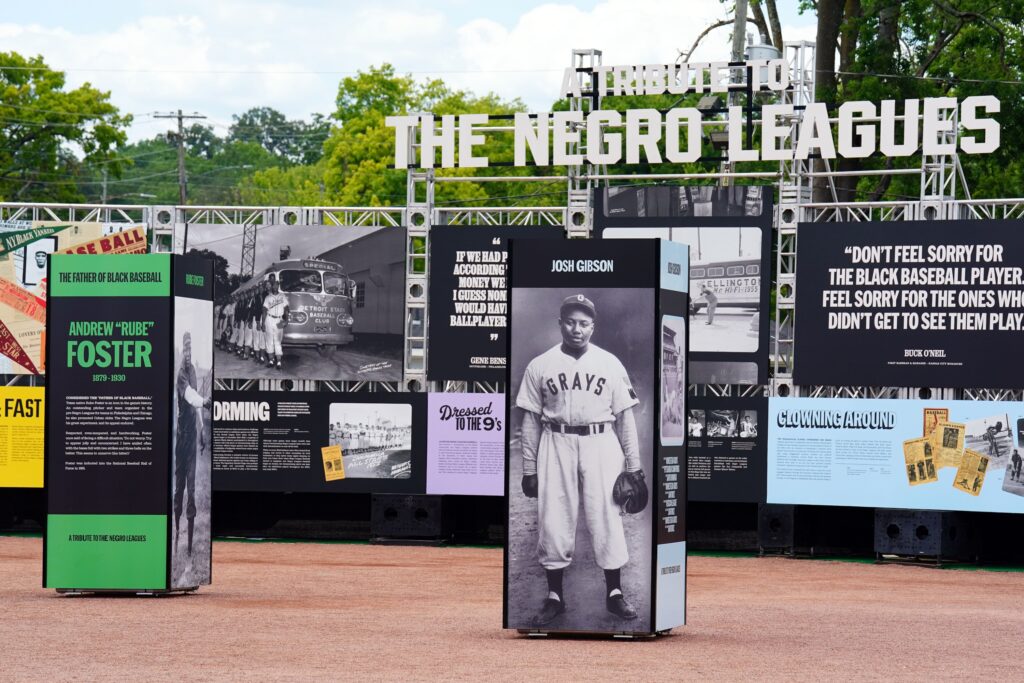

For the first half of the 20th century, professional baseball exemplified the country’s racial segregation. African-American players were confined to playing against one another in the Negro Leagues from 1920 to the late 1940s as they were banned from competing against the likes of Babe Ruth, Walter Johnson, and Ty Cobb in the Major Leagues. Because of the color of their skin, Black stars of the period, like renowned slugger Josh Gibson and speedster James Thomas (Cool Papa Bell), did not have the opportunity to test their elite skills against the white Major Leaguers. That did not change until Jackie Robinson made history with the Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers in 1947. He opened the floodgates for other Negro League trailblazers like Mays, Larry Doby, and Satchel Paige to follow him into the changing MLB, a league featuring some teams that initially were more open to roster segregation than others. Aside from Jackie Robinson, who only played 34 games in the Negro League, it took MLB until 1971, 20 years after the Negro League folded, to make Paige the first representative in Cooperstown. To this day, the baseball Hall-of-Fame has over 300 inductees, yet only 37 of them stem from one of this country’s most impactful baseball leagues.

Known Names

The likes of Robinson, Mays, and Hank Aaron spent very little time in the Negro Leagues before truly making their mark in historic MLB careers. Jackie hit four home runs with the Kansas City Monarchs in 1945 before Branch Rickey signed the explosive athlete to the Dodgers. In 1951, Aaron parlayed his impressive play with the Indianapolis Clowns into a contract with the Atlanta (previously Boston) Braves, the team with which he would bash a record-setting amount of home runs.

In contrast, Doby and Paige both spent more time in the Negro Leagues before kickstarting American League (AL) integration. Doby starred for the Negro League’s Newark Eagles from 1942-1946, leading the team to the title in his final full season (1946). In 1947, Doby signed with the Cleveland Guardians (FKA Indians), becoming the first African-American player in the AL. He excelled in MLB, making annual All-Star Game appearances from 1949-1955. In his first full season (1948), Doby hit .301 with 14 home runs and 66 RBIs, playing a major factor in Cleveland’s World Series triumph. The legendary pitcher Paige, aged 42 at the time, joined Doby on that championship Indians’ squad, achieving a 6-1 record with a 2.48 ERA in 21 games. He spent the next year with Cleveland and then four more years in the Majors, his stuff not waning despite his advanced age. It sure would have been fun to see how Paige, arguably the greatest Negro League pitcher ever and one of the best pitchers of all time, would have fared against the likes of all-time great hitters Ruth, Stan Musial, and Joe DiMaggio.

If Paige was the best pitcher in the Negro Leagues, Gibson was the best power hitter as the Hall-of-Fame catcher routinely blasted monster home runs during his 15-year playing career with the Pittsburgh Crawfords and Homestead Grays. With the integration of Negro League statistics into the MLB record books, the man nicknamed the “Black Babe Ruth” now holds the highest single-season (.466) and career batting average (.372) in MLB history. Because not as much knowledge exists about the Negro Leagues, no one truly knows how many home runs he accumulated, nor the farthest distance he ever hit one. This prodigious talent was robbed of the chance to shine in MLB and team up with or against his white counterpart Ruth on the same diamond.

He is not the only player whose achievements baseball’s history has failed to document. The career achievements of Bell are also semi-shrouded in mystery with limited information about the renowned speedster whose exploits on the basepaths preceded and likely inspired Lou Brock and Rickey Henderson’s record-breaking careers.

Lesser-known Names

While Gibson and Cool Papa Bell each had one outstanding, carrying tool, fellow Negro League standout Oscar Charleston was a five-tool player. One of the league’s first elite players, he constantly batted above .300, sometimes over .400, serving as a reliable run-producer, outfielder, and base stealer on the various teams he played for from 1920-1941.

Similarly, although Paige is the best-known pitcher, “Bullet” Joe Rogan and “Smokey” Joe Willaims were two other Negro League aces. Two-way sensation “Bullet” was one of the faces of the dominant Kansas City Monarchs’ team of the 1920s. “Smokey” was no slouch as people like Cobb thought he would have dominated in MLB, and the hard-throwing Texan often out-pitched Major League stars in exhibition contests. Yet, because both pitchers stopped playing before integration, they are not as well-known as Paige.

More Work Is Needed

Fast forward to 2024 and MLB is still working to address the diversity among the league. African-American players remain the under-represented minority (after a short-lived surge after integration), overshadowed by White and Latino players. Last week’s matchup at Rickwood Field only featured two Black players–Cardinals’ hitters Masyn Winn and Victor Scott II. The Giants’ first baseman LaMonte Wade Jr. desperately wanted to play, but the league denied the team’s request to activate him off the injured list for that game.

Thus, there is much more work to be done. For starters, MLB would be wise to plan more activities to acknowledge American baseball’s racist history, engage and inspire Black players, umpires, and managers, and ensure that last week’s special game was not a one-time experience.

Main Image: John David Mercer-USA TODAY Sports